Youth Resource

The Image of God: The Future

(You may want to do the lesson on “The Image of God: The Concept, An Illustration, & The Impact” before this lesson, or use some material from that lesson as background information.)

This segment comes from Episode 2: Rights + Wrongs.

Modern Westerners take it for granted that every life is valuable. But ideas like equality before the law and the importance of caring for the vulnerable are by no means self-evident. So where did they come from? Why are we so attached to the idea of “inalienable human rights”? This segment looks at how the biblical idea that every human is made in the “image of God” has shaped the way our society today cares for the most vulnerable, and discusses whether a commitment to this idea is necessary for this kind of care to continue into the future.

Videos

-

The Image of God: The future

Can we be good without God?

Transcript

JUSTINE TOH: It took a long time to get to where we are today – to this deep-rooted assumption that people matter. All people, regardless of status, regardless of capacity.

Of course, you don’t have to believe in God in order to treat people this way. And naturally, everyone loves their own grandma. But what about the person who has no one?

For a long time, the worth of those on the margins – the child with a disability, the person with dementia – has been safeguarded by this notion that there’s something divine about even the most broken or powerless person.

There’s something really beautiful about that, about showing care and respect to someone who hasn’t done anything to “earn” it, who isn’t successful or powerful by the world’s standards, who might not even know you’re there.

NICK SPENCER: It’s always worth attending to the way in which we engage with those who are at the periphery or perhaps the weakest point of our society, those who are not able to defend themselves or articulate their own worth.

JUSTINE TOH: The 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche spooked Western culture by accurately describing what Christianity had contributed to it – and what the world without it would (according to him, should) look like.

ACTOR (FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE): Christianity has taken the side of everything weak, base, ill-constituted. Christianity is called the religion of compassion. One loses force when one has compassion. Compassion, on the whole, thwarts the law of evolution, which is the law of selection. It preserves that which is ripe for destruction; it defends life’s disinherited and condemned. In every noble morality it counts as weakness. Nothing in our unhealthy modernity is more unhealthy than Christian compassion.

JUSTINE TOH: We shrink from Nietzsche’s conclusions; rightly, I think. But history tells us that reaction isn’t guaranteed.

NICHOLAS WOLTERSTORFF: It seems to me where the difficulty arises for such a secular account, is when we acknowledge that people who are not capable of rational agency, when we acknowledge that such people still have rights and that we’ve still got obligations towards them, since they’re not capable of rational agency. So, I think it’s the marginal human beings, the truly marginal – those who are in a long-term coma, those who are suffering from Alzheimer’s, the infant who was severely impaired from birth and so forth – it’s those marginal human beings who I think constitute the great challenge.

ROWAN WILLIAMS: I do believe personally it’s quite difficult to sustain the kind of absolute doctrine of human rights in the long run unless there is some notion that human beings relate to something more than just other human beings’ desires and opinions. The religious perspective says every human being relates from the word go to another order, another reality which is the divine, the sacred. Everyone is so to speak plugged into that network. Whatever a society may do, whatever an individual may think, that relationship with the depth of reality is there. Now, it may or may not be true that you can carry on pragmatically believing in human rights without that but it’s a very, very robust anchorage for human rights, if you do think that. And I’m not too optimistic about it surviving indefinitely without something like that.

close

Theme Question

What has been the contribution of Christianity to the idea that all people are valuable, regardless of their status or capacity?

Engage

- Read this quote from Hubert H. Humphrey, former Vice President of the United States, and answer the following questions:

- To what extent do you agree with this quote?

- Why is it important for governments to care for all citizens, including the most marginalised and vulnerable?

- Read this article, “‘Granny dumping’ case to be heard as businessman accused of abandoning American, 76, to get him free care” from The Telegraph, and answer the following questions:

- What is your reaction to Kevin Curry’s decision to “dump” his father? What do you think his motivations may have been?

- In what ways does this case show the high value our society places on caring for the vulnerable?

- In what ways might it also show the opposite?

- Find three images that show something about how the vulnerable are cared for in modern society.

Understand & Evaluate

Watch the segment: The Image of God: The Future

- In the video segment, Justine Toh says, “For a long time, the worth of those on the margins … has been safeguarded by this notion that there’s something divine about even the most broken or powerless person.” Here, she is referring to the idea that all human beings are made in the “image of God”.

- Write a one-sentence summary of what the concept of being made in the “image of God” means. You may want to watch the segment “The Image of God: The Concept” to help you.

- What might be “beautiful” about showing care and respect to someone who isn’t successful or powerful by the world’s standards?

- Read this quote from prominent 19th-century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, and answer the following questions:

- What is your reaction to Nietzsche’s negative view of compassion?

- What worldview seems to be behind Nietzsche’s statement?

- Do you think what he says is logical based on his worldview?

- Rowan Williams describes the Christian notion of every person being made in the “image of God” as a “very robust anchorage for human rights”. He also says that without this worldview, “it’s quite difficult to sustain the kind of absolute doctrine of human rights in the long run”.

- To what extent do you agree with him?

- How might someone who doesn’t believe in God respond to what Williams says here?

Bible Focus

Read Matthew 25:31-40.

- How does Jesus identify himself with the vulnerable in this passage?

- What motivation does this passage give Jesus’ followers for valuing and caring for the poor and marginalised?

Read James 3:9-10.

- Why does James condemn those who praise God but curse human beings?

- How do you think we should treat people if we believed that they “have been made in God’s likeness”?

Apply

- Imagine that Nietzsche has tweeted his views on Christian compassion to you. Write a series of 3-5 tweets replying to Nietzsche, using ideas from this lesson.

- Do you view other people as those who “have been made in God’s likeness”? Can you think of individuals or groups of people you might relate to differently if you saw people this way?

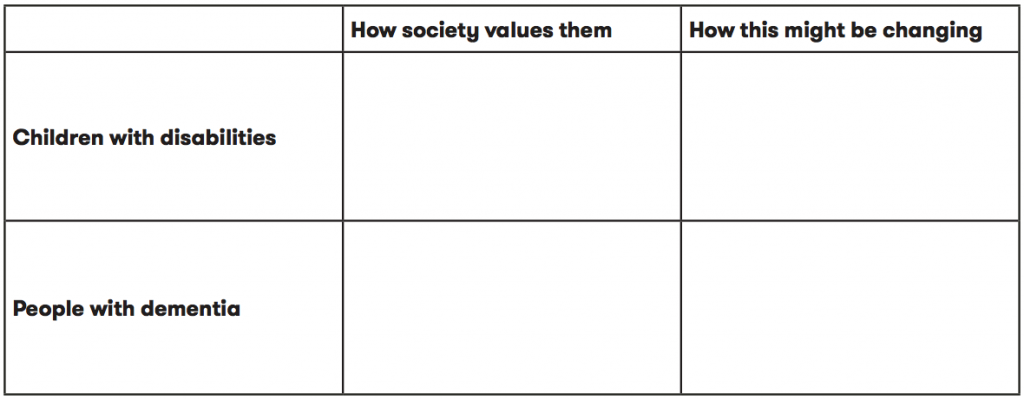

- There are many people who are vulnerable in our society. The video particularly mentions two groups of people: children with disabilities, and people with dementia. How is it evident that these people are valued by our society? How might this be changing? Answer these questions in the table below.

- Hold a debate to answer the question: “Can universal human rights for all people, including the most vulnerable, continue without the notion that human beings are created in the ‘image of God’?”

Extend

- Watch the interview between CPX’s Simon Smart and Helen Thomas titled “Zoe’s Story: Where Life Begins and Ends”. What points does Helen make about the inherent value of human life?