Youth Resource

The Image of God: The Concept, An Illustration, & The Impact

These three segments come from Episode 2: Rights + Wrongs.

Modern Westerners take it for granted that every life is valuable. But ideas like equality before the law and the importance of caring for the vulnerable are by no means self-evident. So where did they come from? Why are we so attached to the idea of “inalienable human rights”? These segments look at how the biblical idea that every human is made in the “image of God” led early Christians to confront the Greek and Roman practice of exposing infants, as well as the practice of slavery.

Videos

-

The Image of God: The concept

Few ideas have changed our world more profoundly than this one.

Transcript

JOHN DICKSON: For most of us today, every life is precious. Valuable in its own right.

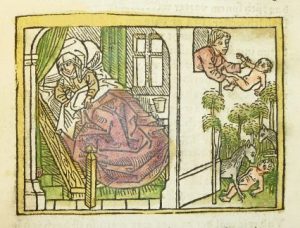

Not so, in ancient times. In the Greco-Roman world – the world in which Christianity first emerged – it was not uncommon to find babies discarded like rubbish on the dumps outside the city.

As a parent, it’s really difficult to imagine someone leaving their newborn in a public place like the local rubbish dump. Some of the babies would have been picked up by other parents looking for another child, or a household servant. But many were left to the elements or the wild dogs. And still others were picked up by local slave-traders looking for some easy flesh.

LYNN COHICK: Children were exposed maybe because they were deformed. Maybe the husband thought the wife was unfaithful, and so the child wasn’t his. Maybe the father divorced the mother, and she decided, rather than let him know that the baby was born, she would just expose the child. Now if you put the child out of the house into a field, or some place outside the town, you were pretty much giving the child a death sentence. We might call that infanticide.

JOHN DICKSON: Expositio, or “exposure” as it was euphemistically called, was widespread in Greece and Rome. Legend has it that Rome itself was established by Romulus and Remus, two victims of exposure, who survived by being raised by wolves, of course!

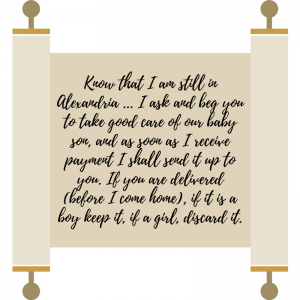

A surviving letter from around the year 1BC from a husband to his pregnant wife in Egypt shows just how un-shocking the practice was.

ACTOR (ROMAN SOLDIER): Know that I am still in Alexandria. I ask and beg you to take good care of our baby son, and as soon as I receive payment I shall send it up to you. If you are delivered before I come home, if it is a boy keep it; if it is a girl, discard it.

JOHN DICKSON: We know why Greeks and Romans practised exposure. But what kind of society made it legal, let alone morally acceptable?

EDWIN JUDGE: Plato, for example, argued that we must dispose of surplus children. He authorised, if you like, infanticide. He doesn’t say how to do it, and he’s only talking theoretically, but he had high principles and one of them was that only the best people should be born, and others are a kind of flaw in the system and should be got rid of.

JOHN DICKSON: It comes down to how we measure an individual’s value. If a person’s worth depends on what they add to society, discarding the useless makes some sense. If our worth depends on something higher, something absolute, it’s a different story. And, arguably, the most absolute claim about human value is that every man, woman, and child is created in the imago Dei – the “image of God”.

The concept of the “image of God” goes right back to Egyptian times. Pharaohs ruled on behalf of the gods, like a son represents a father. Someone like Ramses II was hailed as the very “image of god”.

He was one of the longest reigning kings of Egyptian history, a famed military commander and prolific builder. He was a big deal.

A monument like this – all seven tons of it – was far more than political propaganda – it was almost religion. It was thought to embody not just the presence of the Pharaoh but of the gods. So, a statue like this was declared “the image of God”, worthy of reverence and love.

But there was another way of thinking about this. The people of Israel, Jesus’ homeland, used the expression in a way that would have puzzled most ancient cultures.

The Israelites took this idea and completely universalised, or “democratised” it. They said that everyone, regardless of wealth or status, was a child of God, made in the very “image of God”.

ACTOR (GENESIS 1:26-27): Then God said, “Let us create mankind in our image, in our likeness”. So, God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. God blessed them.

IAIN PROVAN: It’s perhaps the most radical thing that the biblical literature has to say because it fundamentally puts every human being on the same level, so that whichever way you organise society the fundamental ethos is going to be egalitarian.

JOHN DICKSON: For Jews and Christians, every human being enjoyed equal and immeasurable worth.

This had nothing to do with the contribution a person could make to society, and everything to do with the love of the Creator.

Just as a child bears the family resemblance, so every man and woman is made in the “image of God”. Whether rich or poor, powerful or weak, moral or immoral, everyone is a child of the Creator; made for him, loved by him. It’s a unique idea, and it changes everything.

NICK SPENCER: I think probably the most important, identifiable, recognisable thing that people can be grateful for Christianity is when they look in the mirror in the morning. What are you seeing there? It is by no means self-evident. You don’t have a barcode on you that tells you how much you’re worth. You don’t have a barcode on you that tells you anything about your intrinsic identity. The idea of who the human is, someone rather than something, a someone irrespective of the fact they may not be able to afford a mirror to look into in the morning, they are not self-evident ideas. And was the incursion of Christianity into what we call now the classical world, that brought about ideas that in engaging with human beings you are in some way engaging with a bit of God, with an image of God.

JOHN DICKSON: If you happen to think that every human life is infinitely valuable, regardless of capacity or usefulness, that human rights are innate, then you’ve been influenced by the Bible’s teaching about the “image of God”.

close -

The Image of God: An illustration

We head to George Washington’s house for a concrete take on a big philosophical concept.

Transcript

SIMON SMART: This grand old house is a source of great national pride for the citizens of the United States.

Not so much because of its size and architectural beauty, or because it’s the best example of a Virginia Plantation House.

It’s valuable, priceless actually, simply because of who owned it.

This is Mount Vernon, the home of George Washington, the first president and founding father of the United States of America.

The American people have decided Mount Vernon is precious because of its connection with Washington.

Frankly, even if this was a one-bedroom shack, they’d still value it.

Similarly, in the West, people came to value each and every human life because of our connection with God – the idea that we’re made in his image.

Philosophers have tried to find the grounding for human rights and often end up on capacity arguments – a person is defined by their ability to think rationally or be useful. But the moment you consider someone without that capacity, their value drops away, and the argument fails.

But Christianity looked at people and saw something radically different.

It insists that because you’re made in the image of God, you are of infinite and irreducible worth, regardless of capacity.

It’s this universal dignity that grounds the human rights we value so highly today.

close -

The Image of God: The impact

What happened when Christians started acting like every person was made in God’s image?

Transcript

JOHN DICKSON: Christians took this Jewish idea that everyone is made in the image of God and confronted the worst elements in Greek and Roman society. And high on their list was the Greek and Roman practice of exposing infants.

Christians collected abandoned babies and raised them as their own. It was, in effect, the first large-scale fostering program.

PETER HITCHENS: One of the major changes in the world as Christianity supplanted paganism was the end of the deliberate exposure of unwanted children, and indeed the increasing objection to the practice of abortion, because of this fundamental belief that all human life was equally valuable, that we are all are made in the image of God, and therefore cannot destroy each other.

JOHN DICKSON: Christians also developed a special concern for the more than two million slaves in the Roman Empire.

The first Christians had no social power. So, the New Testament contents itself with urging masters to treat slaves as equals, and urging slaves to love their masters.

But as Christians gained in confidence and social influence, they expanded their goals. A Christian text written here in Rome in the second century urges wealthy Christians to use their money, not just to feed the poor, but to buy up “distressed souls”. Slaves.

Instead of expanding their fields and renovating their villas, wealthy Christians were meant to purchase slaves they heard were being mistreated in the local district, bring them into their homes, and treat them as family. In this very early period, Christians couldn’t overturn Roman slave law, but they could modify the experience of slavery from within.

ROWAN WILLIAMS: One of the typical bits of the stories of the saints and the great figures of the fourth and fifth centuries, when they have a religious conversion or when they decide they need to be more serious as Christians, they free their slaves. It’s one of the things you do if you want to show you’re serious. You set your slaves free.

JOHN DICKSON: By the fifth century, Christians began to confront slavery head-on.

Saint Augustine was one of the most important figures of the early church. He was a some-time resident of Rome, and also the bishop of the port town of Hippo, over the horizon. He’s mainly remembered as a towering intellectual, but he was also involved in practical efforts to fight the slave trade that criss-crossed these waters.

In AD 428, in a letter to a church colleague, Augustine tells of the horror of the ancient slave trade and of church efforts to thwart it.

ACTOR (AUGUSTINE): About four months prior to my writing this there were brought in people assembled from various regions and especially Numidia by the Galatian dealers – for they either monopolise the trade or apply themselves to it with special relish – with a view to their being shipped out through the port of Hippo. There was not lacking a believer aware of our custom in acts of mercy of this kind who reported it to the church. Immediately 120 people were liberated by our members. Hardly anyone could keep back tears on hearing the different stories about how they were kidnapped or press-ganged before being handed over to the Galatian slavers.

JOHN DICKSON: It sounds noble now, but at the time, to their Greek and Roman neighbours, this Christian behaviour seemed odd and wasteful.

It’s sadly true that Christians didn’t overthrow the scourge of slavery for many more centuries. It’s equally true that in ancient times they were the only ones doing something practical to subvert it.

ROWAN WILLIAMS: Although Judaism and Christianity begin in the world where, for example, slavery is taken for granted, both of them have what I sometimes called a long fuse. That is, they light a long fuse of argument and discovery which eventually explodes and people realise, you know, actually we should do something about this.

close

Theme Question

Do Christians value individuals, or restrict and oppress them?

Engage

- Find an article or video about a search and rescue mission. Estimate the cost in terms of time, people involved, and money spent on the rescue. What does this tell us about the value of a life?

- On 28 July 2017, British infant Charlie Gard died from a genetic disorder known as mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome (MDDS). In the months leading up to his death, his parents had been engaged in a prolonged legal battle over Charlie’s treatment. Read this BBC article “Charlie Gard: The story of his parents’ legal fight”, and answer the following questions:

- In what ways does this case show the high value our society places on human life?

- In what ways might it also show the opposite?

- Do you agree with the decision made by the court? Why or why not?

- Read this quote by J.K. Rowling from Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, and complete the activities below:

- Give examples of other books or movies that demonstrate this idea.

- Do you agree with Rowling’s quote? Why or why not?

- What do you think a single life is worth?

- Is the value of each human life the same across all cultures and all eras?

Understand & Evaluate

Watch the segments: The Image of God: The Concept and The Image of God: An Illustration

- Sketch how you imagine the place where children were discarded in ancient Greece and Rome.

- What are some of the reasons parents discarded their children?

- What is your reaction to this extract from the letter from a husband to his pregnant wife? What does this tell us about their view on the value of human life?

- Compare and contrast the Egyptian concept of the “image of God” with the Jewish idea.

- How does the analogy of George Washington’s house help shed light on what it means to be made in the image of God?

- What is the basic concept of the “image of God” as it is expressed in the Bible? How is it connected to human worth and dignity?

Watch the segment: The Image of God: The Impact

- How did the concept of the “image of God” shape the actions of Christians with regards to …

- The practice of exposure?

- The practice of slavery?

- Put the following events in order:

- Whenever slave ships came into port, locals told church officials, who mobilised funds and volunteers to free the slaves

- The New Testament urges masters to treat slaves as equals and urges slaves to love their masters

- A Christian text written in Rome urges wealthy Christians to use their money to buy slaves and then free them

- Is there anything surprising about the ways in which the early Christians tried to challenge the Roman practice of slavery?

- Read this quote from Nick Spencer and explain what he means.

Bible Focus

Read Genesis 1:24-31

- What is noticeably different about the account of how God created animals and how he created humans?

- What unique qualities and responsibilities does God give to humans in this passage?

- How does this passage demonstrate the Bible’s view of the equality and dignity of all humans?

Apply

- In the segment, John Dickson says “If you think that every human life is infinitely valuable, regardless of capacity or usefulness, then you’ve been influenced by the Bible’s teaching about the ‘image of God’”. What might an atheist response to this quote be?

- Do you think there are any ways in which our society is starting to lose the belief of the inherent dignity and worth of all people? Give examples.

- Imagine a dystopian future where the following groups of people are no longer valued: children, the elderly, the sick, and migrants and refugees. Write a plot outline and first paragraph of your dystopian novel.

- If you were being marked from 1 to 10 (1 being lowest, 10 being highest) on how you treat other people, what do you think your score would be? What would raise your score?

- Hold a press conference, with some students acting as journalists, and one student acting as the leader of the Police Search and Rescue Squad who is ordering a major operation to search for a lost bushwalker. Ask the “journalists” to come up with several questions challenging the value of such an operation, and ask the “police officer” to justify it, drawing on themes from this lesson.

Extend

- Read this ABC Online article ‘Why we need the Christmas story’ by CPX’s Simon Smart, and write short answers to the following questions:

- How has the Christmas story, as well as the idea of the “image of God”, shaped our understanding of the human person?

- Does the Christian story agree with the idea of the fundamental goodness of human beings? Do you agree with this idea?

- Why does Simon Smart say we need the Christmas story? What do you think about this?