Youth Resource

The Good Samaritan: How a story shaped our world

This segment comes from Episode 3: Rich + Poor.

From decadent medieval popes to modern televangelists with private jets, religion and money can make for an unsavoury mix. But why do we think of charity – care for the poor and the sick – as a good thing in the first place? People in the Graeco-Roman world didn’t think so: they mostly thought the poor and suffering deserved what they got. This segment traces how one of Jesus’ stories – the parable of the Good Samaritan – profoundly shaped our world.

Videos

-

The Good Samaritan

Jesus’ most famous parable had a big influence on the early church – and the world.

Transcript

JOHN DICKSON: The expression “a good Samaritan” is one most of us are familiar with. It comes from a story – a parable – Jesus told about a man who was robbed and left for dead on the treacherous road between Jerusalem and Jericho.

Two religious types walk by – one of them a priest – and they do nothing. Along comes a Samaritan, an outsider, and he’s the one to bind up the victim’s wounds, take him to safety, and pay for his recovery.

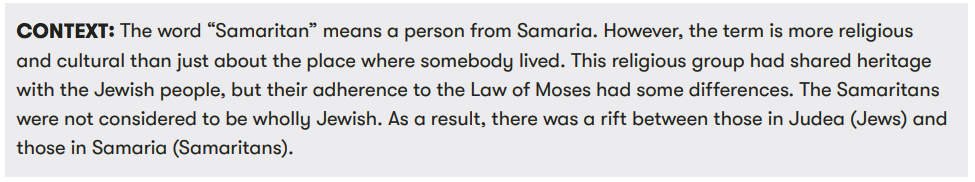

LYNN COHICK: Jesus makes the Samaritan the ethical hero because he is, in that Jewish culture, the absolute anti-hero. It’s the kind of thing where maybe even some Jews would say, “I don’t want your help. I may be taking my last breath, but the last person I want to help me is a Samaritan.”

JOHN DICKSON: Jesus expected his followers to care for people in need, regardless of race, religion, or morality. And by making the Samaritan – not the priest – the hero of this story, he was pointing out that sometimes religion gets in the way of universal compassion. If that sounds like a modern message, it’s because Jesus’ teaching influenced our world more than we realise.

LYNN COHICK: The parable of the good Samaritan is something that just resonates in Western culture. We’ve got hospitals called the good Samaritan. It’s our ideal.

JOHN DICKSON: For the next few centuries Jesus’ followers searched for ever more innovative and effective ways to follow his teaching and redress poverty. By the year 250, the church of Rome was supporting 1500 destitute people a day.

It’s incredible to think that the church’s daily food roster for the poor was as large as the largest civic associations in the Roman empire – the teacher’s guild, the leather workers union, and so on. And Christians were doing this in a period when their own legal status was tenuous at best, and sometimes they were being fed to the lions.

WILLIAM CAVANAUGH: The best kind of care that the church has provided for the world has been when it’s out of power and it’s not worried about ruling but more worried about being on the ground, taking care of the poor and the vulnerable.

ROWAN WILLIAMS: Looking out for the interests of the people who’ve been forgotten – and I think that’s actually one of the things that the church keeps coming back to one way and another. Who’s not here? Who’s not audible? Who’s not visible? They’re the people we need to be in touch with. And in so many societies with huge rates of human casualty you have to say, well, if it weren’t for that community, which is dedicated to looking out for the interests of those that everybody else has forgotten, then it would be an appalling prospect.

JOHN DICKSON: During what’s called “Great Persecution” of years 303 to 312 many churches were destroyed and Christians arrested and killed. Court records of the time highlight just how central charity was to the activities of the early church.

Roman officials burst into the church of Cirta – over the other side of the Mediterranean – hoping there were treasures hidden in the basement, just as there often were in the pagan temples. What they found was a simple storage room for the church’s work among the poor. The official records list the items: “16 tunics for men, 82 dresses for women, 13 pairs of men’s shoes, 47 pairs of women’s shoes, 19 peasant capes, and 10 vats of oil and wine for the poor”. Given Christianity’s rich tradition of charity, I guess you could say they did find the true “treasure of the church”.

JOEL EDWARDS: What is so central to Christian faith, apart from the very important beliefs about the nature of Jesus Christ, his life, his death, resurrection, and his coming again, these things are important, but I’m always amazed by the simplicity of some of the stories Jesus told, the story of the Good Samaritan and how you look out for your neighbour, which is about added value to community. And so I think at the very heart of Christian faith are some yet big ideas about God and the world, but actually, it’s about added benefit to your neighbour – an essential feature of what Christian faith looks like.

close

Theme Question

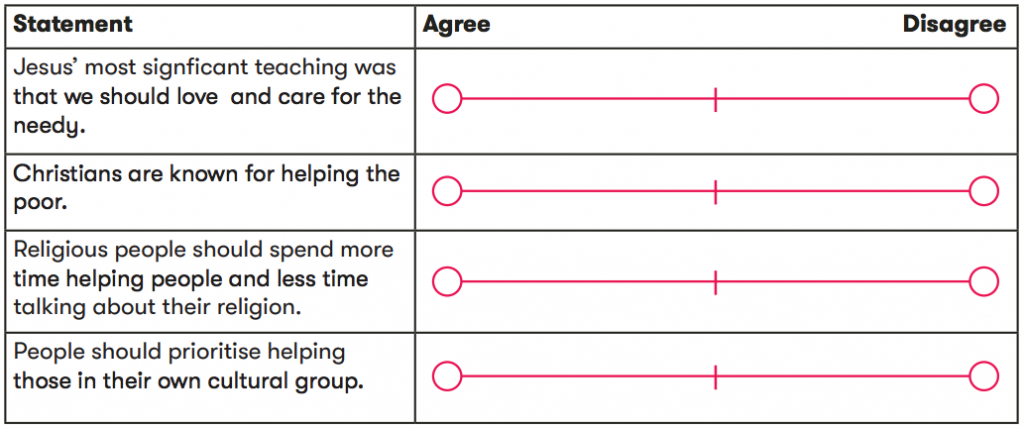

- What are some motivations people might have for looking after the needy?

- Why might some people not make it a priority to care for the needy?

Engage

Understand & Evaluate

Watch the segment: The Good Samaritan: How a story shaped our world

- Why did Jesus make the Samaritan the hero of his story? What point was he making?

- Describe how the parable of the Good Samaritan shaped the way the early church cared for the poor.

- What is your reaction to this quote from William Cavanaugh?

- What did Roman officials find in the basement of the church of Cirta? What might this show us about the priorities of the early church?

- Joel Edwards says that “added benefit to your neighbour” is an “essential feature of what Christian faith looks like”. Do you agree? Why or why not?

Bible Focus

Read Luke 10:25-37.

- What question prompted Jesus to tell this parable?

- In the parable, who …

- Ignored the man who was attacked?

- Helped the man who was attacked?

- Describe the relationship between Jews and Samaritans (use the Context Box and the video to help you).

- Explain how v.27 links with the meaning of the parable.

- Look at the artwork below, “The Good Samaritan (after Delacroix)” by Vincent van Gogh. Explain how the artwork reflects the parable as recorded by Luke.

Apply

- Create a modern re-telling of the parable of the Good Samaritan. Use a setting and characters that are relevant to your own context.

- In the video segment, John Dickson states that “Jesus expected his followers to care for people in need, regardless of race, religion, or morality”.

- Outline why Jesus’ followers today might not always do this well.

- Explain why it is important for Jesus’ followers to continue to care for people in need.

- In NSW, the Civil Liability Act has a section which protects those who act to try to help others in need from being sued if anything goes wrong. For example, administering first aid to a stranger who has had a fall in a shopping centre. This section of the law is called “Good Samaritans”. How do you think the language of “Good Samaritan” ended up in a non-religious legal document?

- Make a poster showing some of the other ways that the parable of Good Samaritan has influenced our society.

- Rowan Williams says that an important application of the parable of the Good Samaritan is “looking out for the interests of the people who’ve been forgotten”.

- Who do you think are some of the “forgotten people” in your school, community, and/or country?

- How could you help respond to their needs?

Extend

- Write an essay in response to the following question:

To what extent has the parable of the Good Samaritan influenced practices of aid and social justice in Australia?

- Listen to the episode “Guess who’s not coming to dinner” from CPX’s Life & Faith Podcast (from 9.30 – 22.57). Write down some examples of how the parable of the Good Samaritan has been used (and misused) by politicians.