Youth Resource

The Colonial Project: Christianity in the Age of Empire

Content Warning: While this segment does not display any graphic images, it does contain mature themes, including references to massacre and rape, and thus may not be appropriate for younger students.

This segment comes from Episode 4: Power + Humility.

The church’s record of holding power – from Emperor Constantine in the 4th century onwards – has involved terrible acts of coercion, exploitation, and abuse. Yet Jesus set an example of selfless service and started a “humility revolution” that fundamentally transformed the West and the way we think about leadership and power. For groups like women and indigenous peoples, what has it looked like when Christians have exercised power for their own benefit? What has it looked like when they’ve exercised it for the good of others? This segment looks at how the Western church was caught up in the project of colonisation and particularly focuses on the church’s mixed record when it comes to Aboriginal Australians.

Videos

-

The colonial project

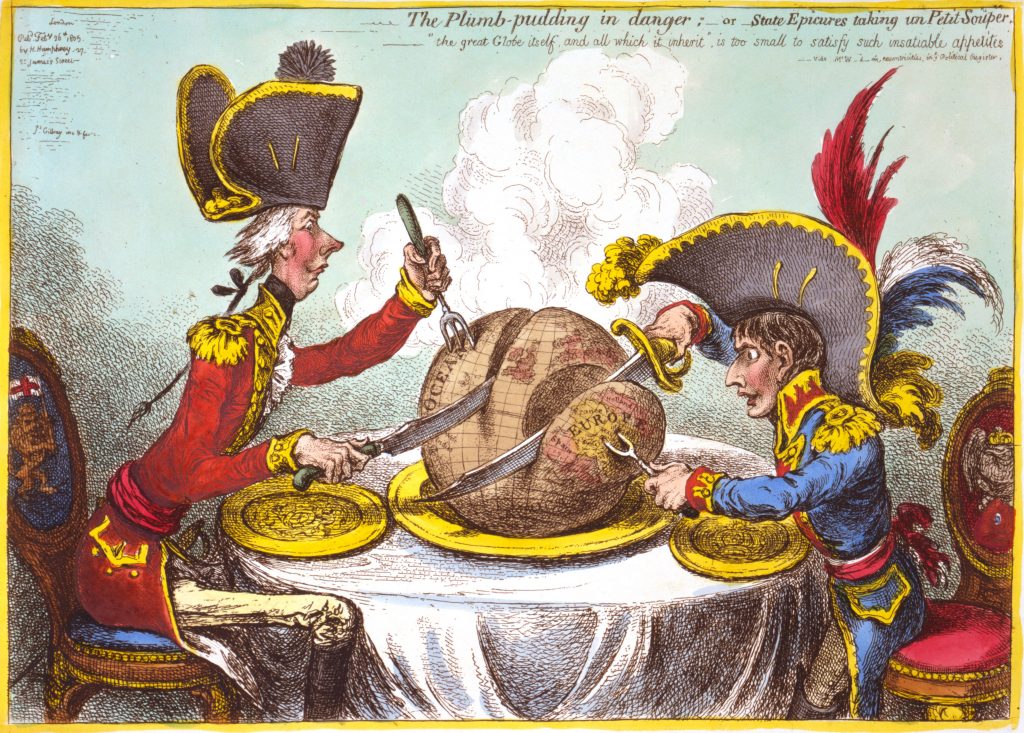

What happened when “Christian” Europe began to extend its influence globally, in the Age of Empire?

Transcript

JUSTINE TOH: As the centuries rolled on, and Christian Europeans left their own shores in the age of exploration, they often left Jesus’ ethic of humility behind. The urge to dominate others proved irresistible.

Australia was no exception, beginning with the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788.

The indigenous nations who inhabited this continent were the custodians of the world’s oldest living culture.

NGARDARB RICHES: Life before the British came was very different. Everyone had the language and the cultures. Every tribe and clan had everything intact, working with the land, the ecosystem, everything.

UNCLE DENIS: In Aboriginal culture and lore, you belonged to the land, you didn’t own it, you belonged to the land so it’s a lot different, so if you belong to something, then you cherish it more, it’s more important to you, that’s where your life comes from, that’s where your living comes from.

JUSTINE TOH: The colony’s original intentions were to “establish harmonious relations with the natives”. But it didn’t work out that way. Diseases, land grabs, and outright massacres led to the annihilation of entire communities. Little more than a century after first contact, the indigenous population had been reduced by up to 90%.

UNCLE DENIS: To lose the land, or to not be associated with the land or belong to the land anymore, you moved off to some other place, was a tragedy you know – it was like losing your family, your dignity, your identity.

JOHN HARRIS: In the simpler terms it meant that they couldn’t get to their waterholes, they couldn’t get to their hunting grounds. But it disrupted society in all sorts of other ways because they were a religious people, all different parts of their land had religious meaning to them. They weren’t able to fulfil the ceremonies, they weren’t able to care religiously and spiritually for their land, and so their whole way of life was made naught.

JUSTINE TOH: In many places around the world, missionaries came ahead of colonisers. But the church was slow to send missionaries to the Aboriginals, or “New Hollanders” as they were known.

But as British people settled here, the church came with them, and its record when it comes to indigenous issues is, like much of Christian history, very mixed.

Churchmen saw little difference between Christianity and Western civilisation. And when the interests of Aboriginal people came into conflict with the economic interests of the colony, plenty of clergy were clear about which side they stood on.

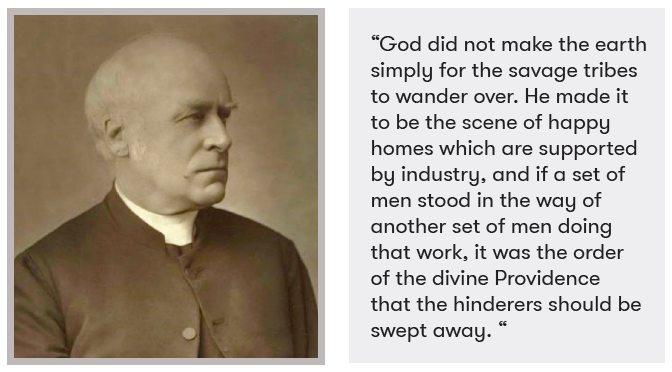

JAMES MOORHOUSE: God did not make this earth simply for the savage tribes to wander over. He made it for the scene of happy homes which are supported by industry, and if a set of men stood in the way of another set of men doing that work, it is the order of divine providence that the hinderers should be swept away.

JUSTINE TOH: But in spite of the apathy and outright racism, there was one point beyond which genuinely Christian people would not go. They simply couldn’t accept the idea that Aboriginals weren’t even human. Their Bible insisted that all people were made in the image of God. White or black, civilised or not, God had made all nations of one blood.

JOHN HARRIS: “God hath made of one blood all nations of the earth.” That is a verse from the authorised version of the Bible, from the book of Acts. And I eventually chose that as the title of my book, “One Blood”, because I just found this verse time and time and time again in the diaries of missionaries, underlined in their Bibles, written in their letters home: “God hath made us of one blood.” Of course, modern translations have wimped out, you know, “God made all people equal” or something or other, which doesn’t sound anywhere near as dramatic; I like the “one blood” because there’s something visceral about that. There’s something visceral about having the DNA, about having the blood of Aboriginal people, and I just found that phrase “one blood” so powerful. And it was a kind of creed, it was a kind of creed of those missionaries. Sometimes I think reminding themselves against the odds that they were equal to these people and they had to take note of that in what they did.

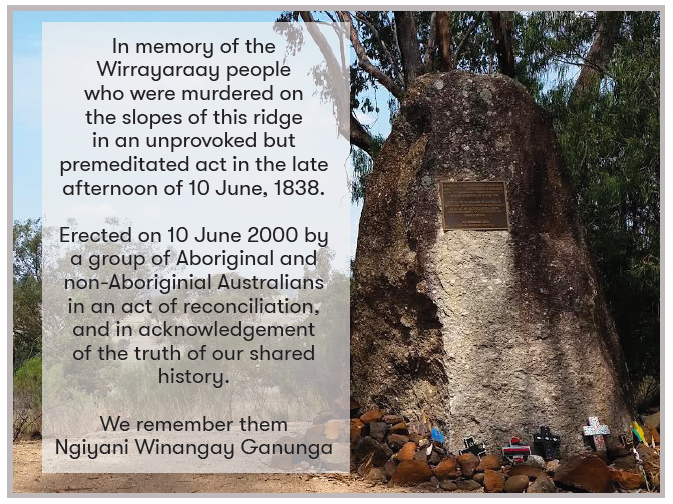

JUSTINE TOH: One of the flashpoints of Aboriginal-settler relations took place in 1838, at Myall Creek in Northern New South Wales. Eleven mounted stockmen approached a peaceful camp belonging to the Wirrayaraay tribe. 35 Aboriginal men, women, and children were roped together, and taken to this ridge. Then the slaughter began.

Children were beheaded, and men and women forced to run between attackers who hacked at them with swords. A girl was spared, so she could be raped. After the drunken celebration that followed, the bodies were dismembered and then burnt.

The massacre was unusual. Not because of its brutality, but because some of the killers were actually brought to justice.

JOHN HARRIS: One of the differences here was that the facts were so well-known and so obvious, and indeed I think people had become so used to the killing of Aboriginal people that they became garrulous; they talked about it and it wasn’t hidden. And for that reason, the Attorney-General wanted to bring these people to trial. Now, he was a committed Catholic and I think that has a lot to do with it. And he brought them to trial, but in that first trial of those seven men, who were defended by funds put in by the northern pastoralists, the jury acquitted them.

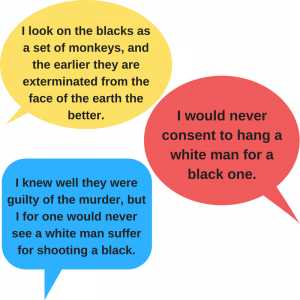

ACTOR (JUROR): “I knew well they were guilty of the murder, but I for one would never see a white man suffer for shooting a black.”

ACTOR (JUROR): “I would never consent to hang a white man for a black one.”

ACTOR (JUROR): “I see the blacks as a set of monkeys. The sooner they are exterminated from the face of the earth, the better.”

JUSTINE TOH: The Attorney-General, John Hubert Plunkett, refused to give up. He filed new charges against seven of the eleven perpetrators, and was backed by clergy across the land.

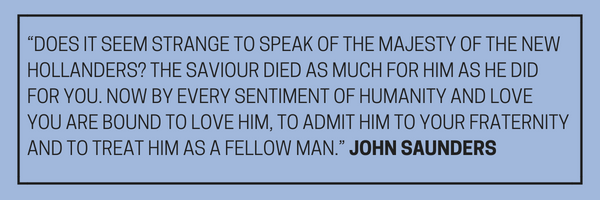

ACTOR (JOHN SAUNDERS): Does it seem strange to speak of the majesty of the New Hollander? The Saviour died as much for him as he did for you. And now by every sentiment of love and humanity and you are bound to love him, to admit him to your fraternity, and to treat him as your fellow man.

JUSTINE TOH: The second time around, seven of the murderers were found guilty and hanged. The result outraged the Australian public.

JOHN HARRIS: People around the missionaries certainly didn’t think of Aboriginal people in terms of any kind of equality. Many of them justified the killing of Aboriginal people by saying that they were “below the white man species” – that’s a phrase from one of the newspapers. They believed that they had a right to oppress, exterminate, evict Aboriginal people from their lands because they were lesser, and sometimes many of them thought they were so much lesser that they were equal to, as they said, “the brute creatures.” They were just not created human, they were not born human. And missionaries had to hold out against that.

JUSTINE TOH: But there’s no denying, the church was very much caught up in the colonial project. It’s a pattern repeated around the world.

close

Theme Question

Does the Church accept and embrace diversity? Discuss.

Engage

- What observations can you make about the following image?

- Choose or draw an emoji to describe how you feel after reading and viewing the extract and videos below, and explain the reasons for your choice.

- The following extract from this 2014 The Sydney Morning Herald article: “These six charts show the state of discrimination towards indigenous Australians.”

“One in five young Australians would move if a person of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent sat next to them, a survey has found. And the same percentage would keep an eye on an indigenous person if they were shopping. More than one in three young Australians also believe that indigenous people are lazy and have been given an unfair advantage by the government.” - “Stop. Think. Respect. Racial discrimination and mental health” from Beyond Blue.

- The following extract from this 2014 The Sydney Morning Herald article: “These six charts show the state of discrimination towards indigenous Australians.”

- Have you ever experienced some kind of discrimination against you or a group you were part of? Have you ever discriminated against someone else or a group of people?

Understand & Evaluate

Watch the segment: The Colonial Project: Christianity in the Age of Empire

- Describe how Indigenous Australians lived prior to 1788.

- Outline the importance of the land to indigenous spirituality.

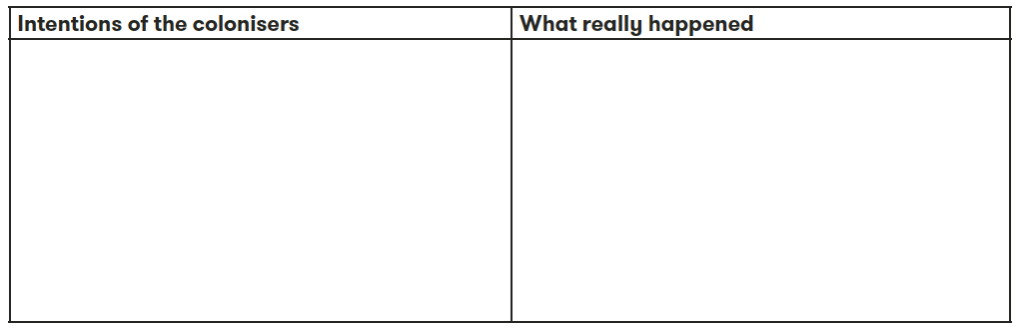

- In the table below, compare and contrast the intentions of the colonisers with what really happened.

- What is your reaction to this quote from Bishop James Moorhouse? What might this show us about the value the church placed on economic development over caring for and protecting Indigenous Australians?

- The bronze plaque at the Myall Creek Massacre and Memorial Site reads:

- What is your reaction to Justine Toh’s account of the massacre?

- Consider the kind of attitudes that seem to have led jurors at the first trial to acquit the accused.

- Outline the underlying beliefs that remarks like these are based on.

- Discuss if/how these beliefs have changed over time in Australian society.

- Explain what motivated Christian leaders, including Baptist minister John Saunders, to fight for the punishment of the Myall Creek massacre killers.

Bible Focus

- This episode quotes an older version of the Bible, from Acts 17:26, which says “God hath made of one blood all nations of the earth.”

- Rewrite this verse in your own words.

- Read Acts 17:24-28.

- What do verses 24 and 25 teach us about God?

- How does v.26 support the idea of all humans being equal?

- Outline God’s desire as stated in v.27.

- The book of Revelation includes a vision of what will occur when the Lord Jesus returns and brings about the new creation. This helps us to think about what “heaven” will be like.

- Read Revelation 7:9.

- According to this biblical text, which ethnic groups will be in God’s perfect new creation (“heaven”)?

Apply

- How do you think it could be possible that Christians, who are supposed to think of all people as made in God’s image, could be involved in the mistreatment of Indigenous Australians?

- Hindsight provides valuable perspective. Most of us will reflect on the actions of the new Australians in the 1800s with disgust. Imagine you are a young person in Australia in 2120 and you are looking back on how Indigenous Australians were treated in 2018. How might you react?

- Churches in Australia today can be very culturally diverse places. Does this sort of community appeal to you? Why or why not?

- Do you think it is helpful to think of all people as being “of one blood”? Create a symbolic image to describe how our society might look different if everybody treated other people this way.

Extend

- Research some of the ways that Christian churches, groups and organisations have been involved in reconciliation and positive actions within the Indigenous community. (As a start, you could visit www.australianstogether.org.au).

- Consider the examples today of discrimination against indigenous Australians from this 2017 SBS article: “10 times Indigenous Australians have experienced ‘everyday’ racism.”

- Imagine you meet someone who engages in this discriminatory behaviour. Write a script of a conversation you could have with them that might help to change their beliefs and behaviour.

- Brainstorm ways you can help to challenge these views in your school or community.