Youth Resource

Power to the people: Luther, Tyndale, and the road to democracy

This segment comes from Episode 2: Rights + Wrongs.

Modern Westerners take it for granted that every life is valuable. But ideas like equality before the law and the importance of caring for the vulnerable are by no means self-evident. So where did they come from? Why are we so attached to the idea of “inalienable human rights”? This segment looks at how the idea that everyone should be able to read the Bible had a huge impact on our world.

Videos

-

Power to the people

The idea that everyone should be able to read the Bible had a huge impact on our world.

Transcript

SIMON SMART: For many of us, it’s difficult to imagine living in a world where the vast majority of people are illiterate.

In the West, written words are the currency of life. By them we access culture, learning, influence – and through them we make our own voices heard.

But in a world where few can read or write, those things belong to an elite few. And everyone else is simply excluded.

That’s what Europe in the Middle Ages was like.

Medieval clergymen kept the power of the written word to themselves, happy to be the gatekeepers of the high culture associated with Latin and the Bible. After all, you wouldn’t want just anyone having access to ideas that, in the wrong hands, could be incredibly subversive.

But change was on the way.

Martin Luther was a German monk, who in 1517 nailed to a church door his famous 95 theses calling for the reform of Christianity.

Luther intention wasn’t to start a new church, but by 1521 he’d been excommunicated for his ideas. And powerful friends of his, who were fearing for his life, stashed him away here at Wartburg Castle. He grew a beard and long hair, and he lived incognito for a year as the German aristocrat Junker Jörg – or “Knight George”.

But Luther didn’t spend that time twiddling his thumbs. He sat down to translate the New Testament into German, and finished the whole thing in 11 weeks!

And the result had a more profound impact than anyone could have imagined.

There were other German translations of the Bible before Luther. But church authorities had banned their publication. Not because they didn’t want people reading the scriptures, but because, they claimed, “the poverty of the German language did not mediate the true meaning of the holy texts.” In other words, German just wasn’t good enough a language for the Bible.

Luther disagreed. He took the high German used by the upper classes and fused it with the everyday language of the people. He wanted to put the ancient wisdom of the Bible into words that people used at home, and in the marketplace.

When translating, he would always ask, “What would a German say in this situation?” He really wanted to provide a Bible for everybody in Germany, and he didn’t think that the people, or their language, were unequal to the task.

When Luther died in 1546, half a million copies of his Bible had been sold. He never requested or received a single pfennig. But the Luther Bible went on to become the most popular book in German households. Its incredibly creative and lively use of language was so influential, it forged for the first time a common tongue for all Germans.

Across the British Channel, the great hero in this translation endeavour was William Tyndale. He was a brilliant scholar who’d thrown away a promising career to put an English version of the New Testament in the hands of his fellow countrymen.

Tyndale very much had the common person in mind. He once got into an argument – a heated argument – with a learned clergyman, who believed it would be better for people just to listen to the teachings of the church rather than read the Bible for themselves.

Well Tyndale was having none of that, he was furious. And he turned to the clergyman, and said, “If God allows me to live long enough, I will cause the boy who drives the plough to know more of the scriptures than you!”

Translating the Bible into the “common tongue” had been illegal in England for more than a century. But Tyndale was undeterred.

He went to Germany to seek help from Luther, and when his English New Testament was finally printed in 1525, it was smuggled into England.

Tyndale paid a high price for his vision. He spent the last decade of his life in hiding, before finally being betrayed by a close friend, and tried for heresy by King Henry VIII.

This celebrated reformer, this champion of the English language, was strangled and then burned at the stake in October 1536. His last words were a prayer: “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes”.

Within just a couple of years, Henry commanded that an English Bible be placed in every parish church in England.

NICK SPENCER: William Tyndale, the earliest and greatest English reformer, wrote one book of political theology called The Obedience of the Christian Man. And it pretty much does what it says on the tin: “the way to respond to authority is to obey it”. But Tyndale the political authoritarian was also Tyndale the evangelical. And Tyndale the evangelical wanted to put, gave his life to putting, an accessible, readable, and it genuinely is an amazingly readable, copy of the New Testament in the vernacular in the hands of everybody no matter who they were. And we mean everybody – not just rich men but women (risky thing to do), ploughboys, tradesmen, that kind of thing. And in doing so he radically undermined political authoritarianism, because that’s like me giving you a copy of the UN Declaration of Human Rights or the Magna Carta or the Bill of Rights or whatever it is and saying to you, “Read it yourself. Inwardly digest. Think about what it means for you and for society”. So not surprisingly, within a couple of years of Henry’s government officials chaining up vernacular Bibles in churches across England, they were passing legislation which was saying, actually, the wrong kind of people mustn’t read them.

SIMON SMART: When the King James Bible came out decades later – a book that would decisively shape English literature and culture – it was based almost entirely on Tyndale’s work.

It’s hard to imagine today how languages like French and German and English – the language of Shakespeare and Austen, Hemingway and J. K. Rowling – could be considered unsuitable for containing important ideas.

At heart, that attitude towards the people’s language is really an attitude towards the people – that the ordinary person is somehow unworthy of learning, or incapable of independent thought.

By translating the Bible, people like Luther and Tyndale were obeying a truly democratic impulse. One with huge implications.

One of those implications was mass education. If you want everyone to read the Bible, first you have to teach them how to read. And that simple task has had a profound effect on our world.

MARILYNNE ROBINSON: I think it’s a very beautiful thing that they were so loyal to the vernacular to create a whole Bible, you know, and to try to reach people who could have no meaningful sense of it at all, and teach literacy at the same time. I think that’s one of the most beautiful things in history.

close

Theme Question

Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) states: “Everyone has the right to education.” Why do you think education is recognised as a universal human right?

Engage

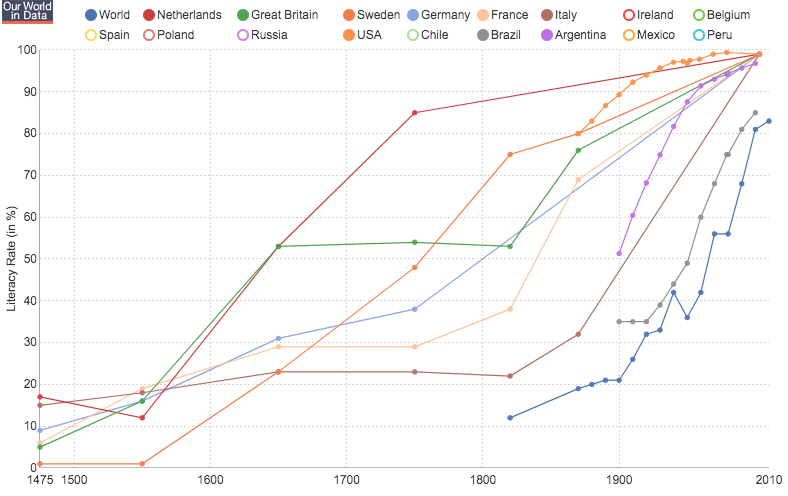

- Look at this graph of world literacy rates over time, from Our World in Data.

Literacy rates around the world from the 15th century to present by Max Roser, Our World in Data, available at https://ourworldindata.org/literacy under a Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence. Full terms at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/.

- How have literacy rates around the world changed over time?

- Choose two things that you find interesting from the graph and share them with another student.

- Why is reading such an important skill?

- Why do you think all schools around the world teach children to read?

- Imagine going about a regular day in your life without knowing how to read. How would you feel? What challenges would you face in different contexts (e.g. at home, on public transport, at school, eating out, etc)?

Understand & Evaluate

Watch the segment: Power to the people: Luther, Tyndale, and the road to democracy

- Describe how medieval clergymen saw their role in relation to the Bible.

- Outline some of the objections church authorities had regarding translating the Bible into local languages.

- Describe the impact in Germany and abroad of Luther’s translation of the Bible in the 16th century.

- What barriers did Tyndale face as he tried to produce an English Bible? What motivated him to continue?

- Write a short dialogue of how the conversation between Tyndale and the clergyman might have gone, ending with Tyndale’s statement “If God allows me to live long enough, I will cause the boy who drives the plough to know more of the scriptures than you!”

- How did the actions of Luther and Tyndale:

- Challenge the attitude that “the ordinary person is somehow unworthy of learning, or incapable of independent thought”?

- Undermine political authoritarianism and promote democracy?

- Impact worldwide literacy?

Bible Focus

Read Psalm 119:97-104.

- Describe the way the psalmist feels about God’s word.

- Make a list of the ways the psalmist gains value from God’s word.

- Which does the psalmist give higher authority to: his teachers and elders, or the word of God? Why?

Read 2 Timothy 3:14-17.

- Paul states that Scripture can make you “wise for salvation”. What do you think he means by this?

- Where does Paul say the Scriptures come from?

- In your own words, outline the ways that the Scriptures are considered to be useful.

- How might these verses have motivated Luther and Tyndale to translate the Bible?

Apply

- Imagine you are William Tyndale about to be tried for heresy and executed. Write a diary entry from the evening before the trial.

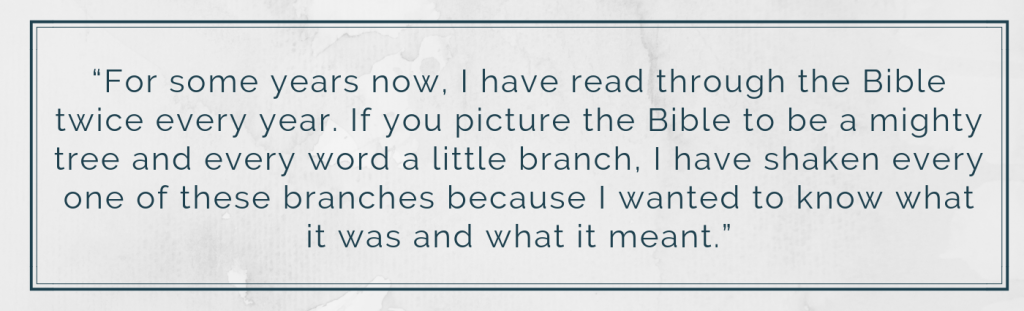

- Martin Luther said:

- Why do you think reading the Bible was so important to Luther?

- The culture in many churches today is for members to read the Bible by themselves on a regular basis. Explain why this practice might be valued.

- In small groups, choose one of the following literacy projects from Bible Society Australia. Read the information on the web page and design a poster about the literacy project to display in the classroom.

Extend

- Read this article, “How Martin Luther and ‘Christianity’s dangerous idea’ made the world we live in” by CPX’s Barney Zwartz. Explain why Luther’s actions could be considered dangerous.