Youth Resource

Human Dignity: Beginning of Life

The videos, articles, podcast extracts, and suggested activities in this Classroom Resource explore how biblical ideas of universal human dignity shape how Christians have seen and treated people at the very beginning of their lives.

This is a sensitive topic where students may have strong opinions, sometimes based on personal experience. Thus, it should be handled with great care.

Videos

-

Life or Death

Sarah Williams reflects on the loss of a child, and how we earn the right to be human.

Transcript

SIMON SMART: Sarah, a number of years ago now, when you had two small kids, you discovered to your joy that you were pregnant with a third child – but then you heard some very devastating news. What was that news?

SARAH WILLIAMS: We went for our 20-week scan, and that moment that you always hear people dreading happened, when the nurse came in and said “There’s something wrong with your child.” They repeated the scan and discovered that our baby had a condition called thanatophoric dysplasia which is a lethal skeletal deformity that would mean that outside the womb, the baby wouldn’t be able to sustain life. So we had to absorb that news.

SIMON SMART: That is grim news. Can you tell me a little bit about that initial moment for you and your husband as you began to process that?

SARAH WILLIAMS: I was completely unprepared for that. Completely unprepared. And what was so striking was how quickly we had to make a decision – there was a decision to be made about whether or not to terminate the pregnancy. And that was a very difficult question for us.

SIMON SMART: Yes, and you eventually did decide to proceed with the pregnancy – perhaps against advice. What made you decide to go in that direction?

SARAH WILLIAMS: I think the decision in the end was about believing that life itself is precious, and that life does begin at formation in the womb, and that all life has some dignity to it. And I felt terribly tyrannised as a woman by the language of choice – the idea that it wasn’t that I could make a choice, it was that I must make a choice. And to have to make a choice about somebody else’s life or death when you’re still reeling from the shock, is a very heavy weight to carry as a woman.

SIMON SMART: I guess you were drawing on your faith, that has a particular vision of what it is to be human, but in that moment, it’s a terribly confronting choice, isn’t it? It wouldn’t have been straightforward, I imagine?

SARAH WILLIAMS: No, not at all. And I knew the ‘right answer’ as a Christian, I knew that I was meant to say “I don’t want to have an abortion”, but actually in the moment the only thing that I wanted to do was just get it over with. That was the only thing I wanted. And I realised in that moment that Christian ethics were not simply about what is propositionally right, but they’re also about loving somebody who is weak and vulnerable and unable to care for themselves.

SIMON SMART: So, in a way Sarah, I guess you were trying to love that child without having met them, but feeling some degree of connection to them, such that you couldn’t at that point anyway feel like you were ok to end it then.

SARAH WILLIAMS: Yeah, I think things like actually finding a name for the baby – so it wasn’t about an ‘it’, but actually a ‘she’, she had a name, she had a place in our family. In some ways I think it was easiest for me, because when you carry a baby, you have a relationship. It’s sometimes harder for a husband or other children to feel a sense of connection to an unborn child. And that was a challenge. So a name was really important. Talking about this person as part of our own story as a family was really important. Taking time to grieve, to think, to dream, to hope – those things were very important for us as a family.

SIMON SMART: What was her name?

SARAH WILLIAMS: We decided to call her Cerian, which is a Welsh name – actually it’s a Welsh nickname – and it just means ‘loved’.

SIMON SMART: What was your experience of the medical side of this?

SARAH WILLIAMS: What I realised very quickly was that the choice not to terminate, although presented as a choice, was systemically problematic. In other words, there was not an obstetric budget for caring for women who were carrying a malformed foetus to term. And that meant that the obstetric care that I received during the pregnancy – there just simply wasn’t a space for that within the hospital facilities. In the end, that was life-threatening for me, because I developed polyhydramnios, which often happens when you’ve got a malformed foetus. It usually sends somebody into premature labour, and for me, it put stress on my heart, and in the end the labour situation was also an emergency situation in which my life was threatened.

And that brought home to me that although on the one hand there’s presented choice, on the other hand, the framework of expectation within the medical profession was very much that a malformed foetus actually is to be terminated. That was certainly the underlying expectation.

SIMON SMART: Did you get a sense then that, as a number of people have commented on, these days the unborn child has to jump through more and more hoops to be thought of as viable?

SARAH WILLIAMS: Absolutely. Yeah I think that’s really crucial. The unborn child almost has to earn their right to be human. And what we’re beginning to mean by that is physical perfection, timing which fits with the desires and expectations of a couple – increasingly we’re understanding children as commodities that fit in to our mentality of acquisition. And so when you’re suddenly confronted with a person who doesn’t fit in, who is malformed, hasn’t got a utility function – what everybody dreads rather than what everybody hopes for – that person challenges the entire value system. And that was my experience of carrying Cerian – that really, I encountered a different way of understanding what it means to be human, and it challenged me.

SIMON SMART: Yes, and so that understanding of what it means to be human, you had a particular version of that – that’s been very influential in our culture – this value of human life no matter what. In what ways might we lose a whole lot if we lose some of that vision which kind of encouraged you in that direction?

SARAH WILLIAMS: Up until that moment in my life, the basic value system that I was operating in was based on achievement – on my ability to marshal my strength towards an outcome of my choosing. And I didn’t use that language, but I had gone through all the hoops that were expected of me and I had achieved. I had my Fellowship at Oxford. I had done the right things. And what was so striking about this experience was the profound experience of love that I had for this child who had never done anything, hadn’t achieved anything. And yet I loved her intensely. And it brought home to me the fact that God loves me because he made me, and because he desires my company. And I don’t have to do a thing to earn that. And my whole value system was reframed and turned upside down, and I really do believe that by terminating the weak and the vulnerable – wiping them out of our society in one way or another – what we’re really doing is we’re setting up a tyrannical system for ourselves. Because we’re really saying that unless we achieve certain things, unless we are ‘useful’, we have no value or meaning. And that, that is the opposite of freedom.

SIMON SMART: Sarah, thank you so much, it’s a very personal and difficult story to tell, but thank you for sharing it with us.

SARAH WILLIAMS: You’re welcome. Thank you.

close -

Zoe’s Story: where life begins and ends

Helen Thomas shares the story of the short life of her daughter Zoe.

Transcript

SIMON SMART: Finding out you’re pregnant is normally a time of great joy. But, when Helen Thomas was pregnant with her third child in 2007, she was told that her baby had a condition that made her “incompatible with life”. Her and her husband decided to go ahead with the pregnancy anyway, and what happened next is a remarkable story. Helen Thomas came into CPX to talk about her daughter Zoe.

Helen, early in 2007, you’re pregnant with your third child, going for a scan – and you get some terrible news. What was that news?

HELEN THOMAS: We were told that our baby had anencephaly, which I where the top of the skull doesn’t close properly and amniotic fluid gets to the brain. And because amniotic fluid’s acidic, it eats away at the brain, these babies literally have no brain – which means in medical terms, they’re “incompatible with life”. We were told she would die at birth, if not before.

SIMON SMART: This was obviously shocking news – how did you and your husband begin to process that?

HELEN THOMAS: We were devastated … But while we were trying to process it, we were also fighting for our baby’s life, because we were told that we really should be aborting a baby with this condition.

SIMON SMART: And you made a choice to go ahead with the pregnancy – tell me why you made that choice?

HELEN THOMAS: Three reasons. We looked at Psalm 139, where we are told that our days are numbered since before the beginning of time by God, and we felt very much that this baby’s days were numbered just like anybody else’s were and that we weren’t in control of how many days this baby was going to live. Following on from that, we very much felt like we didn’t want to choose the day – we didn’t want to be the people that chose the day she was going to die. And, thirdly, we felt very much that if one of our other children was diagnosed with something and we were told they only had 20 more weeks to live, we wouldn’t say, “right, well let’s end it now because then we don’t have to go through the next 20 weeks”.

SIMON SMART: Tell us about the birth. You were expecting Zoe not to live – it turned out differently.

HELEN THOMAS: So, at one o’clock in the morning on the 21st of June, 2007, Zoe was born, and she was born alive, and we were delighted to see that she was breathing! Because I felt very much like I’d held her alive for the whole of the pregnancy and I really wanted Marty to do that independently of me, she was given straight to him and we sat and watched her breathe. And that was an amazing thing to see, because we hadn’t anticipated that was going to be the case.

SIMON SMART: And then she keeps on breathing, breathing, breathing – and it goes on and the life extends much beyond what you could have expected.

HELEN THOMAS: Way longer than we expected! The minutes turned to hours, and the hours turned to days, and the days turned to weeks and months and then years. And she lived till she was four.

SIMON SMART: What was her life like, and what was it like for you as a family caring for her?

HELEN THOMAS: She was highly disabled. So, she couldn’t do anything – she was really just here to be cuddled and loved. She couldn’t move, she could only very slightly move her hands and feet. She couldn’t see, she couldn’t hear, she couldn’t cry. She just laid there, really. She slept and she woke, but she couldn’t communicate with us. But we communicated with her as though she was completely normal, and she came with us wherever we went – holidays, sporting matches, birthday parties, she came everywhere with us.

SIMON SMART: Why then would you say this was a worthwhile life? You very much get the sense from you that you feel like it was.

HELEN THOMAS: Well she couldn’t do anything in the world’s eyes that was an achievement. She couldn’t run or talk, dance or sing or do well in an exam. But she was one of us, and she took her place in our family and we loved and adored her. And she taught us that actually, you don’t have to be good at things, you don’t have to achieve things to be able to be loved by someone. And we felt very much like that – we loved her just as we loved our other children, who can do and achieve things.

SIMON SMART: It can’t be easy, but tell us about her final illness.

HELEN THOMAS: She got pneumonia often so we were very used to her getting very, very sick and we knew that her life was in the balance every time she got pneumonia. And we’d said goodbye to her a number of times actually, she had been so sick.

But this one particular time we knew things weren’t great and we took her to the hospital, and we called our girls in to give her a kiss and a cuddle and we said to them, you know, “We’ve done this before, we don’t know whether she will make it, so tell her you love her and give her a kiss”. And they went home, and Marty and I sat with her, and about half an hour before she died her doctor came in and said, “I think we’re there.” And Marty took her in his arms and I held her hands, and we said to her, “It’s OK to go, Zoe…Go home”. And we thanked God for her and we said to God, you know, “We’re ready, you can take her home now” – and at five o’clock that day, she died.

SIMON SMART: And your sense was that this was a kind of mercy for her, at that point?

HELEN THOMAS: Her life in this world was really difficult. She got really, really sick, often, and heaven is by far a better place for her. For us – we wanted her to stay. Her being gone causes us sadness every day. But for her, yes, this world was a really difficult place.

SIMON SMART: As you look back on this experience, how is your life different because of your time with Zoe?

HELEN THOMAS: I think we’ve learnt a great deal. We certainly have learnt to love our children unconditionally – it doesn’t matter what they can do, it doesn’t matter what they achieve.

I think we’ve learnt to trust God with the big things in life. I think it was up to God whether or not she lived when she was born. It was up to God how long she lived in this world, and it was up to God when he was going to take her home – and I think what Zoe’s life has taught us is that actually, God is in control and we’re not in control. As much as I tried through all of Zoe’s life – through the pregnancy and the delivery and her life – to control things, ultimately, when I look back and I talk through the story, I wasn’t in control at all.

SIMON SMART: Well it is your story; it’s Zoe’s story as well. It was so good to hear it; thank you so much for coming and sharing it.

HELEN THOMAS: Thanks for having me.

close

Articles

-

Sister Act (Extract)

Two Sisters of Life share about their work supporting mothers and pregnant women who feel that their choices are limited.

-

We need more expressions of care for one another

As the bill to decriminalise abortion is debated in NSW Parliament, Laurel Moffatt asks how we might together pursue the “uncommon good”.

-

Unwelcome others: Christmas reframes the divide over abortion and refugees

How the plight of refugees and children at risk of abortion are more comparable than we might think.

-

Life, unedited: Jesus doesn’t need to be made relevant

Mark Stephens on why a key part of the good news of Christmas is that Jesus was once a baby.

Engage

- Reflect on the following question and choose the answer that best describes your view:

- When do you think life begins?

- At conception

- At birth

- Sometime in between conception and birth

- I don’t know

- When do you think life begins?

- Thinking about your answer to Q1, reflect and ask yourself these questions:

- What made you choose the response you chose?

- What reasons might someone have for holding a different perspective?

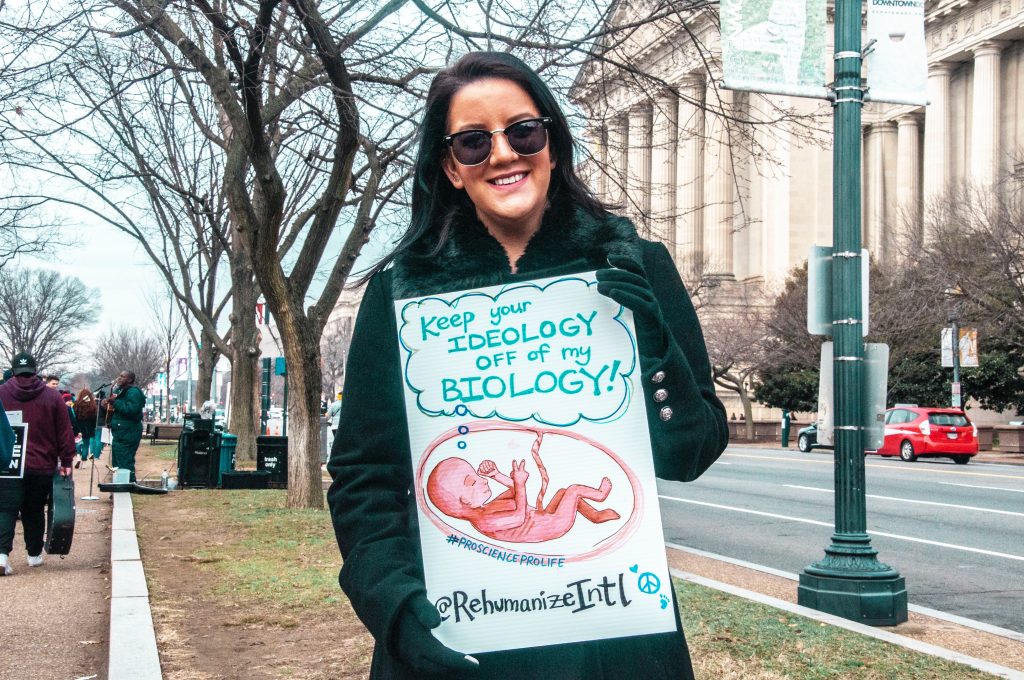

- Look at the following images and complete the See, Think, Wonder Thinking Routine for each image:

- What do you see?

- What do you think about that?

- What does it make you wonder?

Understand & Evaluate

- Watch either the video interview with Sarah Williams Life or death OR the interview with Helen Thomas Zoe’s Story: Where life begins and ends. Complete the following activities, and then share your responses with another student who watched the other video.

- Briefly summarise the woman’s story from the video.

- Using the video transcript, choose one sentence that stood out to you from the video. Why did you choose this sentence?

- What understanding of human life and human value does this video articulate?

- Read the extract from the ‘Sister Act’ podcast episode and complete the following activities:

- Highlight part of the extract that surprises you.

- Write a headline and summary sentence for this extract.

- Imagine you have the chance to ask the Sisters another question in this interview. What question would you ask them?

- Read Laurel Moffatt’s article We need more expressions of care for one another. Think-Pair-Share your response to this quote from the article:

- Read Justine Toh’s article Unwelcome others: Christmas reframes the divide over abortion and refugees and Mark Stephens’ article Life, unedited: Jesus doesn’t need to be made relevant. From what you read in these articles, how does the Christmas story, where “in the person of Jesus, God experiences life from womb to tomb”, speak into the idea of the value of human life from the very beginning?

Bible Focus

- Read Psalm 139:13-16, Jeremiah 1:4-5, and Luke 1:26-45. What do these passages imply about the beginning of life?

- From the passage in Luke, write a journal entry from Mary’s perspective reflecting on the events of this passage and what you imagine her feelings may have been about her pregnancy.

Apply

- As a class, using a program such as Mentimeter, submit words and/or emojis for a WordCloud that summarise the material covered in this class and your reaction to it.

- Think back to Engage Q1 and answer the following questions:

- Has your response changed? Why or why not?

- Has this class helped you to better understand other perspectives on this complex topic?

- What is one thing you want to think about or research further after this class? Write your answer on a post-it note.

Extend

- Listen to the CPX podcast episode ‘Brave as a Bear’ and explore the Brave Foundation website. Write an email to Bernadette sharing your reaction to her story and asking any questions you have for her.