Youth Resource

Curbing Violence: Just War and the Peace of God

This segment comes from Episode 1: War + Peace.

From Jesus’ command to “love your enemies” to the idea of “holy war” is a giant leap. Yet from the Old Testament through to the Crusades and the inquisitions, Christian history is full of violence. Has Christianity been a major contributor to war? How have the followers of a crucified leader managed to get things so wrong? This segment looks at the progression from the early Christians shunning all violence, to the idea of a “Just War”, and ultimately the “Holy War” of the Crusades.

Videos

-

Curbing violence

As Christians gained influence, they came up with ideas like “Just War” and the “Peace of God”.

Transcript

WILLIAM CAVANAUGH: The early Christians for the first three centuries assumed that what Christ’s sacrifice meant was that you would prefer to go to your death rather than shed blood. And so the early Christian church is full of martyrs, and the few Christians that joined the Roman military were most often criticised by their fellows. It’s not until the Roman emperor himself becomes a Christian in the fourth century that Christians begin to develop justifications for the shedding of blood.

JOHN DICKSON: Christians eventually became so numerous through all ranks of society, that they had to form opinions about the harsh realities of public justice, and even warfare.

By the fifth century, 400 years after Christ, there were so many Christians throughout the empire that imperial officials began to consult Christian opinion on matters of state and even on warfare. Suddenly, Christian intellectuals had to do some very quick thinking. And none was more agile, or more influential, than Aurelius Augustinus – Saint Augustine.

Augustine is considered one of the greatest thinkers and writers of the ancient world. He was generally opposed to warfare but he reasoned that under certain conditions war could be appropriate for a Christian ruler. There was such a thing, he said, as a “Just War”.

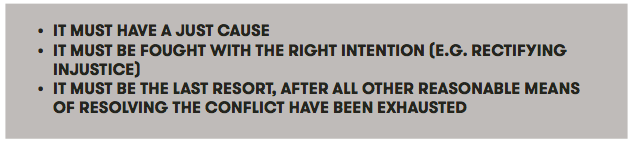

NIGEL BIGGAR: When we think of whether to go to war, the first thing we think about is whether there is just cause. And that would be some kind of grave injustice that needs rectifying. You’ve also got to have right intention, so in intervening am I intending to rectify the injustice? And then because war is a really hazardous and destructive business, you don’t want to do it unless you really, really have to. And if you can find peaceful means of resolving conflict you should do it. Therefore, it should always be a last resort, all other reasonable means of resolving the conflict having been exhausted.

JOHN DICKSON: Augustine taught that a war could be just, but only if it was conducted in self-defence, and with such a high regard for humanity that your enemy, if he lost, was left feeling neither humiliated nor even resentful. I’m not sure how practical that is, but as far as military theories go, it’s nice.

ROWAN WILLIAMS: Now that’s a long way from “Holy Wars”. What we sometimes don’t notice is the slippage between that and, say, the medieval crusading ideal. Augustine is saying, “Look, things are falling apart. The world is pretty difficult. There are circumstances where you have got do what isn’t ideal. If, in order to fight off marauding barbarian tribes from northern Europe, you need to take to battle – well, all right, I suppose. I mean, it’s not a good thing but the alternative is probably worse. And if you are going to do it and still remain some kind of a Christian, then for goodness sake keep in mind the following moral principles.” So, it’s a very grudging concession. It’s certainly very different from the crusader marching off to recover Jerusalem, shouting, “God wills it”.

JOHN HALDANE: There is no clear corresponding tradition in other cultures. I mean there are debates within other cultures about war, but it doesn’t look, as far as we know, as if there is a “Just War” tradition outside of the West. And it is worth saying that there is no tradition of “Just War” thought in the West that arises independently of the Christian tradition.

JUSTINE TOH: Fast-forward a few centuries and medieval Europe is an incredibly violent place. Knights would maraud across the countryside, terrorising the poor, plundering fields, villages, churches.

Christian leaders tried a number of things to curb the violence, or at least direct it into more “productive” channels.

WILLIAM CAVANAUGH: There are things like the “Truce of God” and the “Peace of God” that put certain people, and certain places, and certain times off limits from war during the Middle Ages.

JUSTINE TOH: People like the monks of the Benedictine Abbey at Cluny tried to persuade the knights to stop killing peasants, and each other, and instead, channel their energies into defending the poor and protecting pilgrims.

The bishops would gather large groups of knights and feudal lords in fields outside the city.

They’d tell them that anyone who shed the blood of a fellow Christian was spilling the blood of Christ. And they’d basically force them to take oaths, like this one.

ANIMATION:

Knight: “I will not carry off either ox or cow or any other beast of burden …”

Priest: “And?”

Knight: “I will seize neither peasant nor merchant!”

Priest: “Good …”

Knight: “And I will not take from them their pence, nor oblige them to ransom themselves, and I will not beat them to obtain their subsistence …”

Priest: “And their livestock?”

Knight: “I will seize neither horse, mare nor colt from their pasture …?”

Priest: (sighs)

Knight: “Oh! And I will not destroy or burn their houses.”JUSTINE TOH: Not exactly a high bar!

The bishops also forbade fighting in between Wednesday evening and Monday morning. They did have to form peace militias to enforce the ban though. As a solution it wasn’t perfect, but presumably better than nothing.

These medieval attempts to contain violence had an unexpected outcome. It seems many knights did convert to a more “religious” lifestyle and come to think of their military duties as a form of service to God. It was a development that paved the way for “Holy War” – the Crusades.

THOMAS F. MADDEN: The church had been trying for some time to reduce the levels of violence in Europe which was a very violent place. They had already instituted various programs like the “Truce of God” and the “Peace of God” – these were preached all over Europe to try to reduce the violence levels. The Crusades came out of that reform movement. The idea was to convince these men who were killing each other and killing unarmed people to use the abilities that they had for something that was good. And that’s what led ultimately to the First Crusade.

JUSTINE TOH: We’ve seen quite the evolution, from the non-violence of the early Christians, to the development of a “Just War” theory and now, a full-blown “Holy War”. Taking up your cross, Jesus’ symbol of self-sacrificing love, in order to fight. It’s a pretty disturbing progression.

NICK SPENCER: The reason why Christian history contains so much coercion in there is simply because it has been so unchristian. And that will strike some people as a slippery answer, but it’s true. There is an irony, to put it very mildly, in following the Prince of Peace, who explicitly abjures violence, violently.

close

Theme Question

Jesus taught his followers to love their enemies. In light of this, do you think someone trying to follow Jesus should ever be involved in a war? Why or why not?

Engage

- Look at the diagram of Touch Football rules here.

- What is the purpose of having clear rules for sport?

Why is having clear rules in sport a good thing? - List three other examples in society where having clear rules is important.

- What is the purpose of having clear rules for sport?

- Find or draw an image that represents something about the phrase “Just War”.

- What do you think the term “Just War” means? Can you think of any circumstances where violence or war might be justified and/or necessary?

Understand & Evaluate

Watch the segment: Curbing Violence: Just War and the Peace of God

- Are these statements TRUE or FALSE?

- Christians have always been part of wars.

- Just war theory assumes that going to war is a good option.

- Many early Christians died for their beliefs.

- Most of the Roman emperors were Christians.

- Augustine was very pro-war.

- Summarise Augustine’s teachings about Christians and warfare. How was this different from the actions of the first Christians?

- Rowan Williams describes Augustine’s teaching that a war could be just as a “grudging concession”. What about the context in which this theory was developed do you think made Augustine willing to make this concession?

- Nigel Biggar outlines some of the conditions of a “just war” as:

- What other conditions do you think should be on this list?

- Look at this list of Conditions for a Just War developed by later Christians. Choose one of the conditions listed, and explain why you think it was included.

- List some of the things Christian leaders in medieval Europe did in order to try to curb violence.

- Using the image below, write in a speech bubble some of the things you remember that the knights swore in the animation.

- How did “Just War” theory, as well as medieval programs such as the Truce of God and the Peace of God help to limit violence in medieval Europe? How may they later also have served to legitimise the “Holy War” of the Crusades?

Bible Focus

Read Romans 12:17-21.

- In what manner are God’s people instructed to live?

- Why are Christians commanded to not take revenge?

- What is significant about the phrase “If it is possible, as far as it depends on you” in v.18?

- How could this passage help those in positions of power decide whether to get involved in war or conflict?

Read Isaiah 2:1-5.

CONTEXT: This passage is written by the Old Testament prophet Isaiah, and through poetic, metaphorical language, gives a picture of what God’s future kingdom will look like.

- Draw a picture to represent this scene.

- What might this passage show us about how God sees war and peace?

Apply

- “Just war theory is a positive contribution Christianity has had on the world.” Fill in the table below with supporting and opposing arguments in response to this statement.

- How could the principles of “Just War” theory be applied to modern-day conflicts? Do you think they are good principles?

- Read this article from the Catholic Herald in the UK, “Just war theory should be abandoned, says conference hosted by Vatican.” Imagine you have the opportunity to present to Pope Francis your own submission about whether the church should preserve or abandon the “just war” theory. Write the letter you would write to the Pope.

Extend

- Read this article by Dr Greg Clarke, “Just war and just peace: trying to be just.” Write a ten-point summary of what you learn.

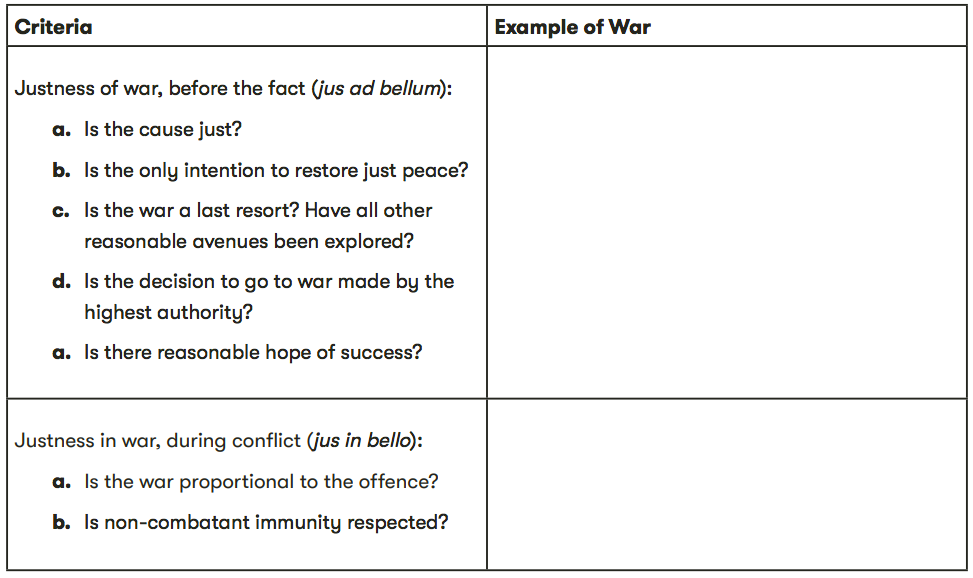

- Consider examples of wars and conflicts in the last 150 years. Choose one to research. Apply the principles of “just war” theory, and outline whether you think this conflict was justifiable based on the jus ad bellum and jus in bellum criteria.

- Write a 300-word article for an online news site outlining your findings from the research that you have summarised in the table above.