Youth Resource

Catholic vs Protestant: The Troubles of Northern Ireland

This segment comes from Episode 1: War + Peace.

From Jesus’ command to “love your enemies” to the idea of “holy war” is a giant leap. Yet from the Old Testament through to the Crusades and the inquisitions, Christian history is full of violence. Has Christianity been a major contributor to war? How have the followers of a crucified leader managed to get things so wrong? This segment looks at the 30-year period known as the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland and discusses the complicated ways in which religion was caught up in the conflict.

Videos

-

Catholic vs Protestant

The Troubles in Northern Ireland are often cited as evidence that Christianity leads to conflict.

Transcript

SIMON SMART: The question of religious violence hasn’t gone away.

This is Belfast, Northern Ireland. The scene of some truly ugly clashes between Catholics and Protestants. Often cited as evidence that Christianity inevitably causes division and bloodshed.

But, it’s complicated.

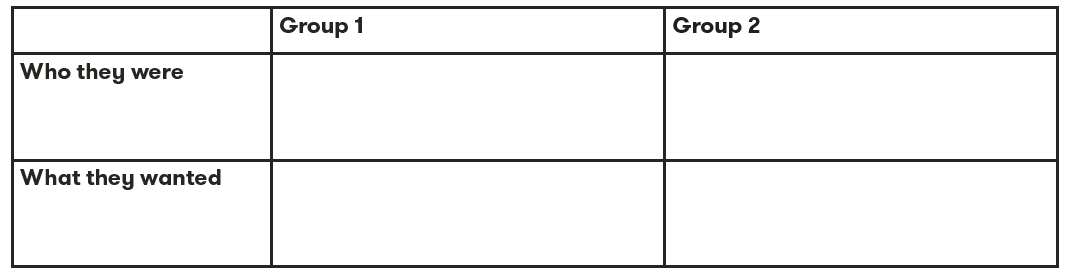

The period known as “the Troubles” began in 1968 and lasted for 30 years. On one side of the equation were the Unionists, also known as Loyalists – the Protestants. They were mostly of British descent and wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of Britain. On the other side were the Nationalists, or Republicans – the Catholics. Their stated goal was to join the Republic of Ireland, which had won its independence in 1921.

Jim lived through it, and now takes tourists around significant sites.

CONVERSATION:

Simon: So, you would have been a young man…

Jim: I was a young man, well yes, 1961 I was born, so I was 8 years of age just coming into the start of the conflict, and that was it.

Simon: You grew up.

Jim: You grew up very quickly. Yeah, I always say that 1997-98 was the first time in my life I’d ever seen peace.

Simon: And so that really dominated life?

Jim: Oh yeah, oh yeah. when I used to get up out of bed in the morning my first thought was: how do we avoid being murdered by the murder gangs, OK? Also, how do we avoid the British Army? From the harassments and stuff like that. And also how do we attack the British Army? But the change being today that when my kids get out of bed in the morning they say, well we have to go to work to get our mortgage paid. Do you see the change?SIMON SMART: It’s fair to say that religious identity has been caught up in the struggle. So how do people who claim a Christian faith, reconcile what happened here with what they believe?

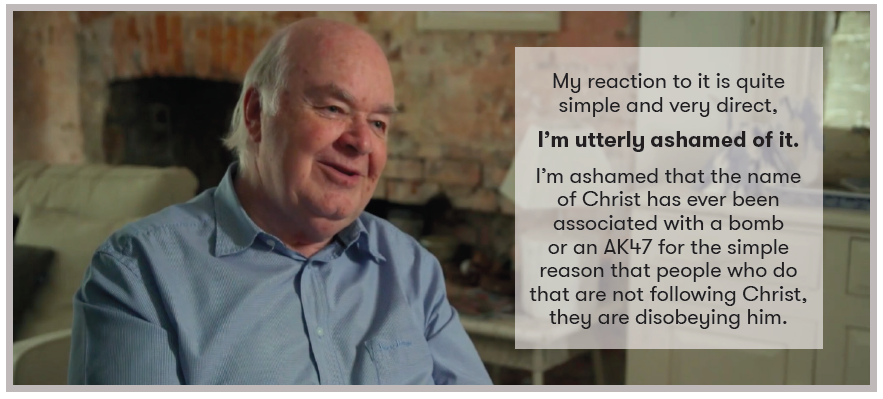

JOHN LENNOX: I’m often asked, how is it possible to be a person who was born and lived in Northern Ireland and still remain committed to the Christian faith? Because I grew up in a situation where my parents lived in a town that was divided, and my parents who were Christian but were not sectarian believed that every man and woman is made in the image of God no matter what they believe, so he put that into practice by employing equally across the Protestant/Catholic divide and we were bombed because of that. So, I’ve some experience of this kind of thing.

And my reaction to it is quite simple and very direct – I’m utterly ashamed of it. I’m ashamed that the name of Christ has ever been associated with a bomb or an AK47, for the simple reason that people who do that are not following Christ, they are disobeying him.

JIM: I’ve always said religion was used too readily to cover this conflict. Because if we think about it here, you’re not seeing one thing about anything religious here. You see that? There is no crosses on that wall, there’s no other stuff like that. This is about a war of independence. In 1979 the Pope got down on his knees here, and said, “Please, please, stop the violence”. It continued on. OK? Also, remember the Queen of England on many, many occasions, she appealed to the Protestant paramilitaries, the Loyalist paramilitaries to stop murdering people. Again, they didn’t listen. So, religion was never taken on board by the paramilitary leaders. Do you understand? They never, ever stopped to think murder is a mortal sin as we say in the church. No they didn’t.

SIMON SMART: The Troubles came to an end on Good Friday 1998, when the key parties reached a peace agreement after 30 years of conflict. However, security walls, euphemistically called “peace lines”, still separate key Catholic and Protestant neighbourhoods.

Often, conflicts that we think of as religious, turn out to be, when we look more closely, about much more than just people’s spiritual beliefs. But there’s no question that religion, when used as an identity marker, can be a potent force in ramping up an “us versus them” mentality.

ROWAN WILLIAMS: There are plenty of circumstances where for Christians, as indeed for Muslims, religion is a really, really good alibi, a really good banner to march under. If there’s a conflict that’s basically about something else, it’s terrifically helpful to make it a religious conflict because it reinforces your own righteousness. But actually, it’s not true. It’s simply not true that the majority of human conflict then or now is religiously based. It can be religiously cloaked, it can be religiously justified, but it’s a big claim to say that it’s religiously motivated. And I don’t think it’s a claim that can be sustained.

close

Theme Question

- How could religion be a powerful motivator for violence?

- Why might religious people resort to violence?

Engage

- Describe your school house system.

- How does your house system create a sense of belonging and inclusion?

- How does it create a sense of us vs them conflict?

- Imagine if another house sabotaged yours in a way that made you lose an important competition. Write a scenario that describes the possible escalation of events that could occur.

- Find a recent news story about an act of violence where religion was involved.

- What sort of event do you think of when you hear the title “The Troubles”? Write a paragraph describing your imaginary historical event.

- What observations can you make about these images of murals that depict something about the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland?

- Listen to the song “Sunday Bloody Sunday” by U2, and read the lyrics. What further insights does this give you about the experience of the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland?

Understand & Evaluate

Watch the segment: Catholic vs Protestant: The Troubles of Northern Ireland

- Who were the two groups clashing in Northern Ireland and what did they want?

- How was the childhood of Jim the taxi driver different to yours? What would it have been like to grow up with Jim’s concerns?

- Jim argues that religion was “used too readily to cover this conflict”. What evidence does he give?

- Rowan Williams says that turning a conflict that is mainly about something else into a religious conflict helps you reinforce your own righteousness. How was this true of the “Troubles”?

- What is your reaction to this quote from John Lennox? Do you think Christians today should be ashamed of the “Troubles”?

Bible Focus

Read 1 Peter 3:8-12.

- List three instructions given in this passage.

- Why does Peter say these instructions are good to follow?

- Identify how Jesus displayed the qualities and values in this passage, and write them on the mind map below.

- In what ways do the values in this passage, and the actions of Jesus, contrast with the actions of those involved in the “Troubles”?

Apply

- Imagine you are John Lennox’s parents just after their shop was bombed. Write an “open letter” on social media addressing those who bombed the shop. Draw on themes from 1 Peter 3:8-12.

- Imagine you have been given the opportunity to paint your own wall mural in Belfast to encourage peace. Draw your mural, and explain how you chose your design.

- Watch this video comparing the biggest fears of children in Syria with those of their peers in relatively safe countries. What are the biggest differences?

- Imagine you are growing up in a conflict zone. Write a letter to an imaginary pen-pal in a safe country sharing about your biggest fears and your hopes for the future.

- Hold a debate on the topic “Were the ‘Troubles’ in Northern Ireland religiously motivated?”

Extend

- Read this homily of Pope John Paul II from his 1979 mass in Drogheda, Ireland. Make a poster outlining what the Pope calls the people of Northern Ireland to do, and the Bible verses and ideas he uses to appeal to them.