Christianity has always been heavily contested in Australia.

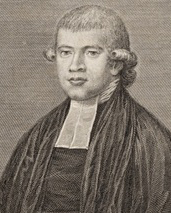

Friday is the anniversary of the first church service ever held in our nation by the first chaplain to the colony, Reverend Richard Johnson, on February 3, 1788.

Johnson was a complete afterthought of the British Home Office — and he did not have an easy time of it in the new colony. The early Governors were not always on his side; one insisted that church start 6am on Sundays, to get it out of the way, and more than once ordered his soldiers to march out in the middle of the sermon.

The first church in Australia — which Johnson built with his own money — was burned down under suspicious circumstances.

The first church in Australia — which Johnson built with his own money — was burned down under suspicious circumstances.

A parable, perhaps, of Australian ambivalence toward religion?

The text for that very first sermon came from the Psalms: “What shall I render unto the Lord for all his benefits toward me?”

From the point of view of 800 convicts who’d just arrived on the other side of the world after eight months chained on a prison ship, it may have seemed a strange choice — what benefits?

But it also hints at why, despite everything, Australians seem to retain a quiet attachment to Christian faith. Half the population still call themselves Christians; half rate faith as “very or somewhat important”. Less than four per cent of Aussies think we’d be better off without Christianity, and 68 per cent believe Jesus is the most important figure in history.

The text Johnson chose expresses a truth that is the Bible’s unique and essential contribution to the history of ideas. Contrary to popular belief, the truth is this: Christianity is not about morality in pursuit of divine reward, but about gratitude in response to God’s grace.

That was the first Christian truth proclaimed on our shores.

It’s a concept that’s foreign not only to the worlds of business, sport, and so on — where performance equals reward — but most religious philosophies as well.

This may be the best-kept secret of Christianity — that goodness is motivated by what God has done, not by what I’m required to do.

One story that illustrates this dynamic perfectly is that of convict Joseph Samuels. He was a petty thief who received a sentence of seven years transportation to New South Wales.

In 1803 in Sydney, he was involved in a brawl that left a man dead. He was promptly tried and sentenced on the Friday, and on the following Monday led out to the gallows (where the Four Seasons hotel now stands), and hanged — three times.

The first time, the rope broke and he fell to the ground.

The second rope frayed and unwound itself until Samuels, semiconscious, was able to prop himself up with his feet.

Believe it or not, on the third try, the rope again snapped.

Everyone stood dumbfounded, wondering if the hand of the Almighty was behind it.

The Provost Marshall sped off to the Governor, explained the situation, and returned to the gallows with an official reprieve.

The write-up in the Sydney Gazette concludes: MAY THE GRATEFUL REMEMBRANCE OF THESE EVENTS DIRECT HIS FUTURE COURSE.

In Joseph Samuels’ case, it didn’t quite work that way — he was last seen three years later, off Newcastle, stealing a boat with a gang of prison escapees.

But the Christian message is that we each make this decision in response to God’s goodness to us: “What shall I render unto the Lord for all his benefits toward me?”

That was the first Christian truth proclaimed on our shores. My guess is that it’s also why Aussies — with all our ambivalence toward religion, and towards institutions in general — have proven not quite ready to let go of Christianity and the influence it’s had on our society ever since.

This article first appeared in the Daily Telegraph.

Dr John Dickson is an historian and author and is the Founding Director of the Centre for Public Christianity.