Religion plays a huge part in war – whether genuinely held or muttered as an insurance policy. For some it might be the immediacy of war makes them realise something they missed in “normal” circumstances, writes Natasha Moore.

On May 7, 1915, during the second week of the Gallipoli campaign, Lance Corporal Elvas Jenkins was working alongside the other men of the 2nd Field Company Australian Engineers when a Turkish shell exploded nearby.

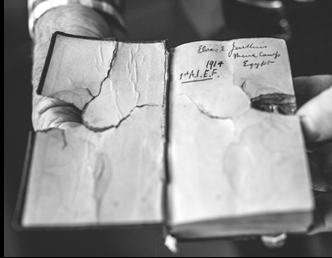

The 27-year-old Elvas was hit directly over the heart, but not killed. Instead, the lead shrapnel bullet that struck him lodged in a French volume of the New Testament plus Psalms that he had picked up while on training in Alexandria and was carrying in his breast pocket. It entered the back of the book, passing through the whole book of Psalms, the letters of Paul and John and Peter, and the Acts of the Apostles. It stopped just short of the Gospels.

There are, proverbially, no atheists in foxholes, and anecdotes like that of Elvas and his bullet-pierced Bible are the stuff of which battlefield superstitions are made. Research conducted recently at Cornell University deduced, from surveys of 949 World War II infantrymen, that the soldiers’ reliance on prayer increased dramatically – from 42 per cent to 72 per cent – as combat intensified.

Of course, few would equate desperate deals offered to a half-believed-in deity under circumstances of extreme stress with anything approaching genuine faith. (Not that such appeals have always proven hollow: Martin Luther, famously, became a monk on the strength of a vow made while caught in a fierce storm.)

Yet, interestingly, follow-up surveys of a different group of veterans 50 years after the war continued to show links – though not straightforward ones – between soldiers’ experience of combat and their religious behaviour. Those who described their war experience as negative attended church 21 per cent more often; those who described it positively attended 26 per cent less often. Whether the trauma of war made soldiers more religious, or whether already religious soldiers responded differently to combat, the researchers could not say.

That there are in fact atheists in foxholes, metaphorical or literal, goes without saying. Indeed, no doubt some atheists are made under the trauma of combat. The Military Association of Atheists and Freethinkers even maintains a roster they explicitly call Atheists in Foxholes (as well as in cockpits and on ships) in order to highlight the honourable service of non-religious military personnel.

On the flip side, how much meaning might we reasonably concede to a statistically significant increase – or decrease – in religious belief under the conditions of armed conflict? American writer James Morrow is quoted as saying that, “‘There are no atheists in foxholes’ isn’t an argument against atheism, it’s an argument against foxholes”. In other words, is there any reason why the instinctive response of a frightened person in an intense, life-threatening situation might be more reliable than their perceptions of reality under “normal” circumstances?

Well, perhaps, yes. In a lecture C.S. Lewis gave to undergraduates at Oxford just weeks after the outbreak of World War II, he spoke of one of war’s (potentially salutary) side effects as its capacity to bring home to us realities we can otherwise mostly ignore:

What does war do to death? It certainly does not make it more frequent; 100 per cent of us die, and the percentage cannot be increased … Yet war does do something to death. It forces us to remember it. The only reason why the cancer at sixty or the paralysis at seventy-five do not bother us is that we forget them. War makes death real to us…

Lewis, in line with a long tradition of Christian and other philosophical thought, interpreted the immediacy that war lends to life and death as corresponding, in some way, to a reality often obscured by the hum of our daily lives when not in crisis. “We see unmistakably the sort of universe in which we have all along been living,” he suggests, “and must come to terms with it.”

It may, after all, be worth heeding the instincts of those in foxholes. British Army chaplain John Lewis Bryan wrote about his experience of Japanese POW camps in Malaya during World War II that the “one request of all ranks” was for a Bible. Those few copies available had to be loaned out for short periods; at Chungkai camp (one of the hellish death camps on the Thai-Burma railway), demand was so high that Bibles were lent and returned on an hourly basis.

By 1944, more than a hundred Protestant services alone were being held every week in Changi, and chaplains even established a theological college in Malaya for prisoners wanting to prepare for ordination. Bryan wrote afterwards:

How many officers and men openly stated that it was their Religion … which kept them sane, when everything men hold dear, was lost. For many, it was their first experience of the saving and keeping power of a living Christ … For all it was a knowledge deep and abiding that Christianity works. No mere theory could have survived the experience of those years of captivity.

Elvas Jenkins, by the way – the Anzac whose Bible saved his life – survived the whole 1915 Gallipoli campaign only to be killed by a German sniper the following year. He was among the first Australians to die at the Somme; possibly the first Anzac killed on the Western Front.

Elvas Jenkins’ Bible still contains the bullet that pierced through its pages at Gallipoli.

Before the war, he had been in training for the Methodist ministry; after the war, he hoped to become a local preacher. As for many Anzacs – and for many Australian servicemen and women since – his faith was not a mere cry for protection, a kind of insurance policy. It was no mere theory; it “worked”. Not because it spared him from death (as Lewis points out, none of us are spared from death); but because it was for him a wellspring of comfort, fortitude, and solid hope amid the darkness, horror – and, yes, the reality of war.

For more about Elvas Jenkins, chaplains from WWI onwards, and many other stories of Australian soldiers and their experiences in war, visit the Bible Society’s Their Sacrifice campaign website. You can see Elvas’ Bible – with bullet still intact – at the Their Sacrifice exhibition, opening in Sydney’s CBD this week and touring Australia over the coming year.

Natasha Moore is a research fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity. She has a PhD in English Literature from the University of Cambridge.

This article first appeared at The Drum.