Only 48 per cent of Australians say they believe in ghosts or the possibility they may exist, but 69 per cent say the same for the soul, according to new research.

The survey of 1000 people, carried out by McCrindle Research for the Centre for Public Christianity, asked respondents about their openness to the existence of a range of spiritual realities: ghosts, miracles, angels, a higher power/God, the soul, ultimate meaning or purpose in life, and life after death.

The results suggest that, as a nation, we may not be as sceptical as we think we are.

In an interview in 2005, the poet Les Murray was asked how comfortable he felt with being “an eccentric Australian voice, a rural poet speaking for an urban culture, a Roman Catholic speaking for a largely secular people”. He responded:

“I just speak as I am. I am a Catholic and I don’t believe that other people are necessarily secular. I think that intellectuals are mostly secular or are required to pretend that they are. But broader people are very varied …”

As a nation, we may not be as sceptical as we think we are.

This new survey backs up Murray’s intuition.

For example, on the question of miracles: roughly a third of people (31.2 per cent) responded “I believe this exists”; almost another third (29.1 per cent) said “I am open to the possibility that this exists”. Some opted for “unsure” or “unlikely”, but only 13.8 per cent were willing to say they did not believe there’s any such thing as a miracle.

The young and the restless

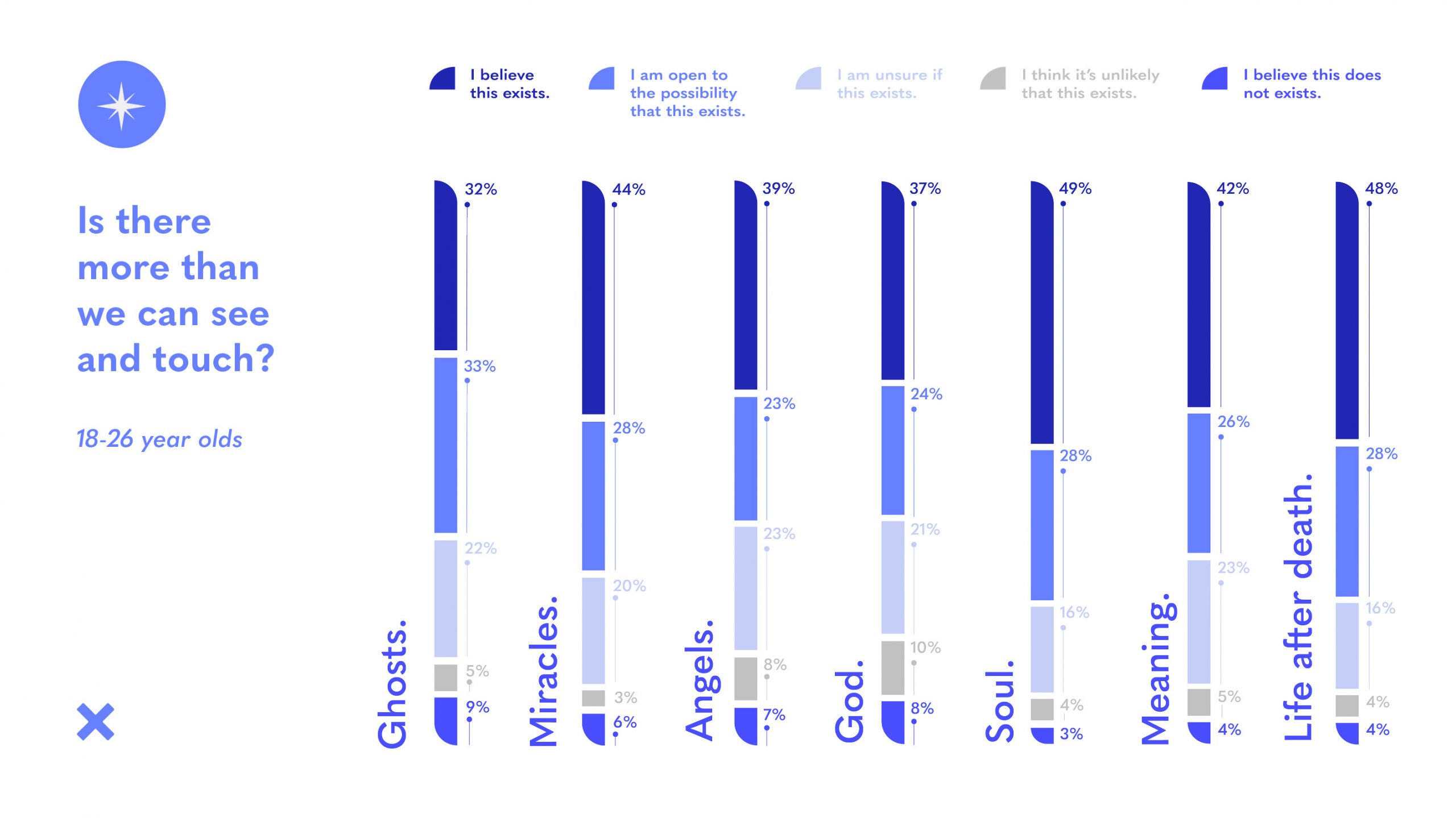

Surprisingly, perhaps, it was the youngest age group — 18-26-year-olds — who expressed the most openness to the non-material : 49 per cent said they believe in the soul, and 48 per cent in life after death (in both cases, another 28 per cent were open to the possibility).

The percentage who said “I believe this does not exist” about any of the options never rose to double digits for this cohort (9 per cent for ghosts, only 4 per cent for life after death).

By contrast, the oldest age bracket (76+) were much more sceptical: a full 40 per cent said they do not believe in ghosts, and 28 per cent dismissed the possibility of life after death.

The gender disparities will be less surprising to some. Men were on average more than twice as likely as women to tick the “I believe this does not exist” box.

Women were markedly more willing to profess belief.

When it comes to the existence of God or a higher power, men and women said they believed or were open to it at almost the same rate. But for the rest, women were markedly more willing to profess belief: 50 per cent to 38 per cent for the soul, 38 per cent to 30 per cent for life after death, 34 per cent to 26 per cent for angels.

This tracks with persistent trends, across a number of religions and cultures, which associate women with higher religiosity and see atheist groups skew male. American sociologist of religion Rodney Stark muses:

“Every religious movement I’ve ever seen any data on was disproportionately female … we don’t really understand why it is, although my student Alan Miller had a brilliant insight in saying, we should stop asking why women are more apt to be religious and ask why men are more apt to be irreligious. And he suggested that, why are men more apt to be criminal? That it’s kind of the same thing, it’s risk-taking, it’s short-sighted behaviour, and that men are more prone to it. It may even be biological for all we know.”

Soul-searching

Australians are most united (as we see in comparable surveys elsewhere) in the idea that we have or are souls — that we are more than the stuff of which our bodies are made.

Overall, 69.7 per cent of respondents said they either believed in or were open to the existence of the soul, with 14.7 per cent unsure, 5.7 per cent thinking it unlikely, and 9.9 per cent saying they do not believe it exists.

While the concept of the soul may traditionally be embedded within a religious belief system, the fact that belief in or openness to it persists at higher rates than for associated concepts like God (57.9 per cent) or life after death (59.6 per cent) suggests that it taps into something important for 21st-century Australians, especially for young people.

Jamaican theologian J. Richard Middleton explains that the soul as popularly conceived — often as a kind of essential self, distinct from the body — is more of an ancient Greek idea than a Christian one. His account helps us understand why it might be attractive today:

“For Plato, I think, the notion of a soul was some point of stability and universality in the world. Because the world is a flux, everything is passing away, but the soul is this immaterial part of you that never changes — it just is you, and it’s eternal. I think people need something that’s beyond this world to cling to, something transcendent. And if you don’t have God, you’re going to find a substitute. I think soul functions as a God-substitute in our world, as something to cling to.”

A negative slant could interpret our attachment to the soul as in keeping with the narcissism of contemporary life; a more generous one might see in the data the outlines of a deep-seated intuition that we matter, in spite of how fragile and fleeting our lives are.

Middleton is blunt about where he thinks we’ll find what we’re looking for: “I would say go to the real source, look for God. Soul is a pale second-best, in my opinion.”

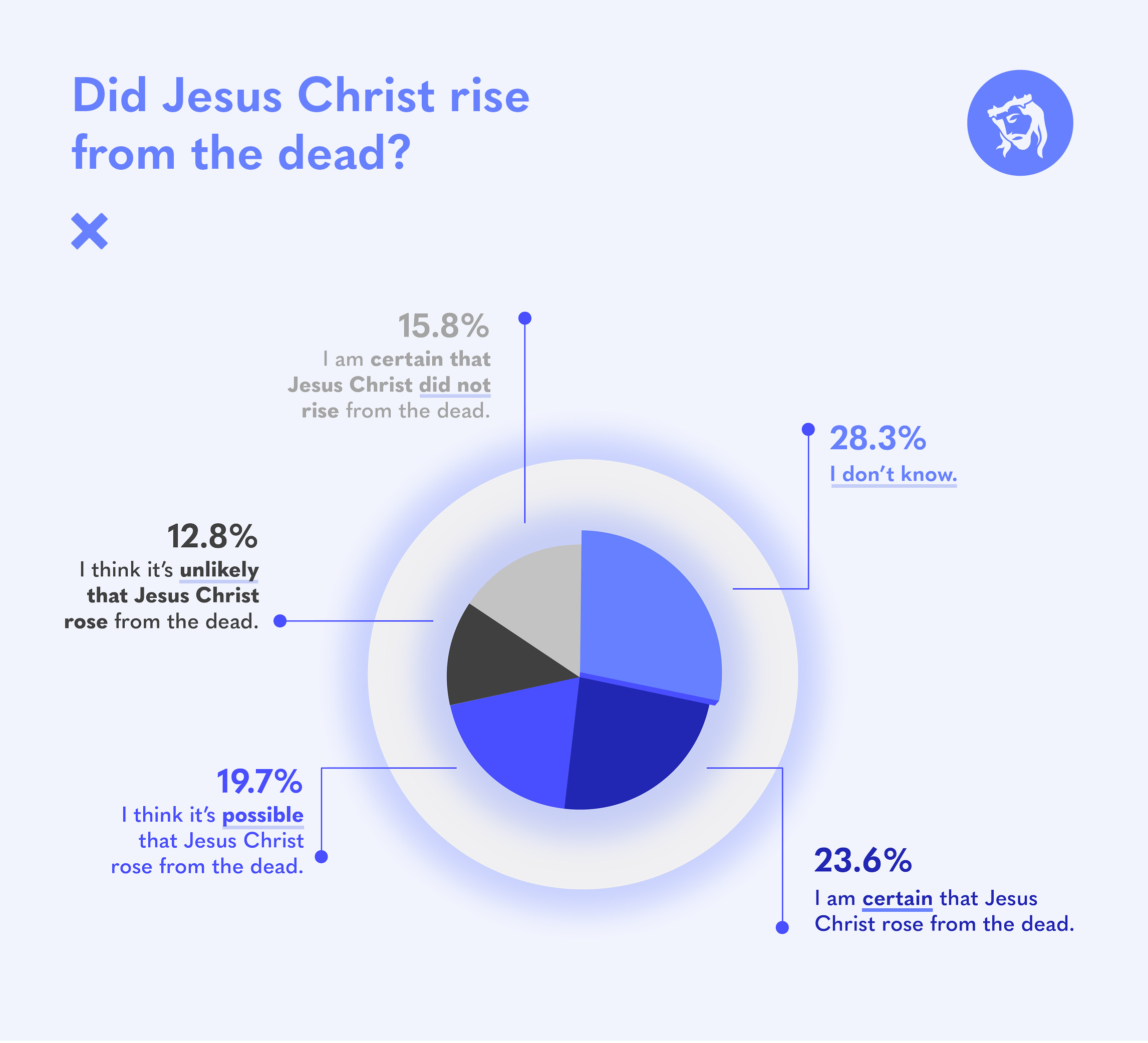

Not that people are necessarily closed to the old sources. In a separate question, respondents were asked for their view this Easter on the claim that Jesus Christ rose from the dead: 23.6 per cent said they are certain this happened; 15.8 per cent are certain it didn’t. Others thought it possible (19.7 per cent) or unlikely (12.8 per cent).

But the most popular answer, at 28.3 per cent, was “I don’t know”. There’s a humility to that that Les Murray might appreciate. As he wrote in his poem, Church:

“The wish to be right

Has decamped in great numbers

But some come to God

In hopes of being wrong.”

Natasha Moore is a research fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity.

This article first appeared at ABC News.