In 2009 Csanad Szegedi, vice-president of Hungary’s far-right, virulently anti-Semitic party Jobbik, was elected to the European Parliament and wrote a book called I Believe in Hungary’s Resurrection.

Then he found out he was Jewish. His maternal grandparents, in fact, were both Auschwitz survivors.

Szegedi’s life, along with all his certainties, collapsed. He was forced to resign from Jobbik. He became an Orthodox Jew; he grew a beard, started wearing a kippah, learned Hebrew and had himself circumcised. He burned thousands of copies of his book, and emerged as an activist against anti-Semitism in Europe. He has migrated to Israel with his wife and two children.

As with our biology, so with our history: where we come from matters for who we are – sometimes in unexpected and inconvenient ways.

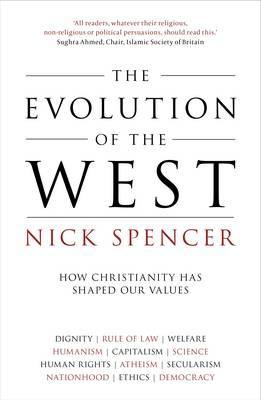

“History writes historians just as much as historians write history”, notes Nick Spencer in his new book, The Evolution of the West: How Christianity Has Shaped Our Values. “The presuppositions of an age, the shadows it lives under, the light it thinks it grows towards: all inform how it narrates its past.”

“History writes historians just as much as historians write history”, notes Nick Spencer in his new book, The Evolution of the West: How Christianity Has Shaped Our Values. “The presuppositions of an age, the shadows it lives under, the light it thinks it grows towards: all inform how it narrates its past.”

Spencer, Research Director at the Theos think tank in London, deftly exposes our collective amnesia about the Christian roots of everything from human rights to the Scientific Revolution to the rule of law and even atheism itself. His rich, complex origin stories also make clear why that forgetfulness matters.

Most fundamentally, of course, it matters because accurate history is better than the made-up or distorted kind – in other words, because truth is better than error. But it also matters for pragmatic reasons: because if we don’t understand why things are the way they are (for better and for worse), it makes it much harder to conserve what we like and fix what we don’t. It matters, too, because one-sided history makes for a more belligerent, polarised, contemptuous public discourse.

It matters because a flattened, selective version of our own history can make us like Szegedi: badly mistaken about who we really are – and liable to excesses of zeal in entirely the wrong direction.

Don’t worry; Spencer’s (appealingly slender) volume is no “Judeo-Christian values” pep rally. He navigates neatly between, on the one hand, those who want to trace everything good about the modern era to the eighteenth-century Enlightenment and the “emancipation” of the West from its religious shackles; and on the other, triumphalist Christian attempts to connect the dots directly from Bible verses to contemporary political, social and ethical realities. Both narratives contain at least kernels of truth, but the history is inevitably more complicated than we think.

This even-handedness is a welcome public service. It’s all too common now for people on either side of a question to seize the truth they have and elevate it to the whole truth. This makes for poor history, and poor civics. It’s like being that spouse who escalates everyday arguments to absolutes: “you always do this” or “you never do that”.

“Secular moderns often have a tin ear when it comes to the religiosity of history”, writes Spencer. But “if Christians of the present think Christians of the past unanimously spent their time campaigning volubly for democracy, welfare, rights and the Scientific Revolution,” he suggests, “they should spend some time reading the Christians of the past”.

Take William Tyndale, a leading sixteenth-century English Reformer, “one of the least democratically minded Christian thinkers in the English tradition” – and one of the most important figures in the development of democracy in Britain. Tyndale was an extreme political authoritarian; but he also believed that the ploughboy should have equal access to the Bible with the most learned clergyman. His ideas of spiritual egalitarianism could not but contribute (eventually) to the case for political democracy – though such a development would have horrified him.

Take William Tyndale, a leading sixteenth-century English Reformer, “one of the least democratically minded Christian thinkers in the English tradition” – and one of the most important figures in the development of democracy in Britain. Tyndale was an extreme political authoritarian; but he also believed that the ploughboy should have equal access to the Bible with the most learned clergyman. His ideas of spiritual egalitarianism could not but contribute (eventually) to the case for political democracy – though such a development would have horrified him.

“Tyndale the political theorist,” writes Spencer, “was matched – and badly undermined – by Tyndale the evangelical.” His contribution to democratic government was accidental, but not arbitrary. He could not control the outcomes of his radical ideas, set loose on the world. The Bible, as C. S. Lewis might have put it, is no tame lion.

This accidental-but-not-arbitrary thread runs through The Evolution of the West. The metaphor in the title is no throw-away expression. Biological evolution, Spencer points out, is popularly imagined as “a smooth, linear, even intentional progress line” when in reality it’s circuitous, fraught with coincidences, dead ends, unintended consequences. History is like that too. Many of the things we value – democracy, equality before the law, anti-slavery movements, empirical science – were far from inevitable.

But this is not to say that, were we to rewind the whole thing and let it run again, our world would be completely unrecognisable. The idea of “convergence” – that, given the same conditions and constraints, the same things (eyes, wings, claws, brains, tool-use) evolve over and over – implies that certain things were probable, if not certain, from the start.

But frankly, in the case of Western culture, not without Christianity. Above all, without the linchpin idea that humans are made “in the image of God” – a complete break with ancient understandings of who mattered and why – we could not have arrived at human dignity or equality, at the very idea of “the individual”, at democracy or human rights or universal education. As with evolution, the right building blocks had to be in place for any of this to happen.

The parallel with biological evolution is apt in another respect: it’s not over yet. We haven’t “arrived”. But getting the questions “where do we come from?” and “who are we?” straight is crucial if we want to be active and wise participants in where we go from here.

Natasha Moore is a Research Fellow with the Centre for Public Christianity. She has a PhD in English from the University of Cambridge and is the editor of 10 Tips for Atheists … and other conversations in faith and culture.

This article first appeared at ABC Religion & Ethics.