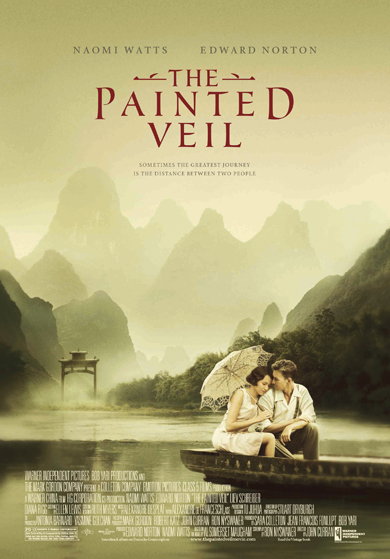

Hollywood films usually end in marriage, not begin with it—though I’m sure couples who have been married for any length of time will declare that the real journey isn’t the walk up the aisle, but the walk after it. In its depiction of marriage The Painted Veil is interested in the latter. Beginning the film with the nuptials of Walter (Edward Norton) and Kitty Fane (Naomi Watts) the film not only inverts the order of conventional Hollywood fare but also reverses the emotional journey of husband and wife: the couple don’t fall in love and then get married; but must first marry and only through staying together do they fall in love.

The film is based on the 1925 novel of the same name by William Somerset Maugham. Kitty, a bored and spoilt London socialite, only marries bacteriologist Walter Fane to escape her horrid mother. Not long after Walter’s work takes them to China, Kitty begins an affair with sleazy diplomat Charlie Townsend (Liev Schreiber). When Walter discovers her adultery he delivers her an ultimatum: marry her lover, or set off with him, Walter, to a remote area suffering a cholera outbreak. Since Walter knows Charlie will not leave his wife, Kitty ends up miserably tied to her resentful husband who burns with hurt at Kitty’s betrayal.

The film is based on the 1925 novel of the same name by William Somerset Maugham. Kitty, a bored and spoilt London socialite, only marries bacteriologist Walter Fane to escape her horrid mother. Not long after Walter’s work takes them to China, Kitty begins an affair with sleazy diplomat Charlie Townsend (Liev Schreiber). When Walter discovers her adultery he delivers her an ultimatum: marry her lover, or set off with him, Walter, to a remote area suffering a cholera outbreak. Since Walter knows Charlie will not leave his wife, Kitty ends up miserably tied to her resentful husband who burns with hurt at Kitty’s betrayal.

The enmity between the couple becomes increasingly hostile until Kitty, lonely and marooned in the isolated community, pleads with Walter to stop punishing her. She asks, ‘Do you absolutely despise me?’ to which Walter coldly responds that it is himself he despises ‘for allowing myself to love you once.’ Behind that chilly, cerebral façade the doctor is revealed to be nursing his broken heart.

The film suggests Walter is so bitter that at some level he desires Kitty’s death—why else demand she accompany him to a cholera-infested region! Walter’s vindictive resentment provides a stern picture of judgement. In the Bible the book of Hosea similarly pictures God as a wounded and angry husband, betrayed by his people who have committed spiritual adultery by wandering after foreign gods.

To indict Israel’s conduct God bids the prophet Hosea to take an adulterous wife; consequently the spawn of that union names God’s fury and pain at the breaking of the covenantal relationship between Him and His people Israel: Jezreel, which means ‘God Sows’ or ‘God Scatters’; Lo-Ruhamah, ‘Unloved’; and Lo-Ammi, ‘Not My People’ (Hosea 1:4-9). In the book of Hosea God’s ferocious promises to destroy the Israelites for their unfaithfulness depict the rawness of His hurt at being so betrayed.

However that’s not the end of the story, but its beginning. Bidden by God Hosea divorces his wife Gomer but then takes her back, symbolising God’s promise to one day take Israel back in love, even at great cost to Himself. The book of Hosea ends with the prophet pleading with the Israelites to seek forgiveness; in return God ‘will heal their waywardness / and love them freely, for my anger has turned away from them’ (14:4). Like God, in The Painted Veil Walter’s anger turns from his wife. But this journey does not come about solely through Kitty’s regret, which is inspired by her coming to admire and gradually care for her husband.  Walter also acknowledges he married Kitty on false pretences, believing that his love for her would one day be reciprocated. In acknowledging their mutual failure as husband and wife Walter and Kitty discover their shared sympathy and learn to forgive each other. In the process, they begin to fall in love, emulating another image of matrimony found in the bible.

Walter also acknowledges he married Kitty on false pretences, believing that his love for her would one day be reciprocated. In acknowledging their mutual failure as husband and wife Walter and Kitty discover their shared sympathy and learn to forgive each other. In the process, they begin to fall in love, emulating another image of matrimony found in the bible.

In the book of Revelation New Jerusalem is pictured as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband (21:2). The gospels describe Jesus as a bridegroom (Matthew 25:6; John 3:29), and heaven a vast banquet like a wedding feast (Matthew 22:2). The scene in Revelation is the prelude to eternity where, we are told, God and His people will experience the ‘profound mystery’ of relationship. In the book of Ephesians this is described in the terms of a man’s union with his wife, as they become ‘one flesh’; Paul reminds us, however, that ‘I am talking about Christ and the church’ (5:32). In its expression of commitment to persevere in love and honour a lifelong attachment between man and wife, earthly marriage is to reflect the heavenly union of Christ and His people.

In the book of Hosea the prophet’s children name God’s judgement: God Scatters, Unloved, and Not My People. It is a testament to the strength of what becomes Walter and Kitty’s ‘profound mystery’ of relationship that though at the conclusion of The Painted Veil Kitty bears what is likely the son of her lover Charlie, she names the boy for her husband: Walter.

In a time where one in three Australian marriages can be expected to end in divorce The Painted Veil is an argument for earthly marriage which remains committed despite a couple being in or out of love, in sickness or health, in the throes of antagonism or adoration. During interviews for the film Edward Norton recounted that older couples had told him how moved they were at the film’s depiction of marriage and the centrality of forgiveness to Walter and Kitty’s relationship. Witnessing Walter and Kitty’s enmity evolve into compassion, respect and love allows a deeply moving, redemptive love story to emerge: a parable of God’s love which remains steadfast and true despite human frailty.

Justine Toh is a doctoral candidate in Critical and Cultural Studies at Macquarie University. Her research explores Hollywood film and American memorial culture in the light of the September 11, 2001 attacks.