“Is there a God?

Of course not.

What is the meaning of the universe?

It doesn’t have any.

What is the purpose of life?

Ditto.

Is there a difference between right and wrong, good and bad?

There’s not a moral difference between them.

What is the nature of the relationship between the mind and the brain?

They’re identical. The mind is the brain.

Is there free will?

Not a chance.”

So proceeds the colourful riff of philosopher Alex Rosenberg from Duke University, in the brilliant documentary series Why are we Here? which aired on Fox’s History channel last Saturday night and will be followed by three more parts in coming weeks.

The series follows acclaimed documentary maker and presenter David Malone, travelling with Oxford Professor of Physics Ard Louis, as they chew over big questions around meaning, purpose and the nature of the universe.

The series follows acclaimed documentary maker and presenter David Malone, travelling with Oxford Professor of Physics Ard Louis, as they chew over big questions around meaning, purpose and the nature of the universe.

This is quality documentary making, and the richly complex nature of the subject matter is handled adroitly, engagingly, and – importantly for a Saturday evening – accessibly. Malone, an atheist, and Louis, a Christian, meet with leading mathematicians, philosophers, neuroscientists, physicists, biologists and cosmologists on their journey. It’s a fascinating dialogue and these two accomplished guides make for excellent companions.

In Episode 1 Alex Rosenberg, along with Oxford chemist Peter Atkins, clearly articulate answers to life’s biggest questions by placing their faith firmly in the domain of science. Both men adhere to Scientism: an influential philosophy which takes the crucial scientific concept of reductionism (breaking things down to their component parts in order to understand how things work) and applies this to every part of life and existence.

In this way of thinking everything – and I mean everything – needs to be explained from the bottom up. The things that can’t be explained must be discarded.

“There are no deeper explanations than those that science provides and the mistake is to be dissatisfied with scientific explanations and to try to seek deeper ones,” says Rosenberg.

“We are a hiccup on the way from one oblivion to another oblivion,” adds Atkins.

The only reliable knowledge is scientific knowledge, according to Atkins – and while we are not there yet, eventually science will have all the answers to any sensible question we could ask.

It’s clear from early in the series that the atheist David Malone is just as confronted by, and dissatisfied with, the notion that the universe and all of us in it are nothing but atoms and molecules as is his less sceptical counterpart Ard Louis.

While reductionism has been a crucial element of “doing science”—discovering that every atom of hydrogen is the same around the universe for example—the temptation to apply that to every aspect of life is problematic, and this too is explored in the documentary. We might concede that from a certain angle, we as human beings are complex animals or elaborate computers. But most people resist the totality of that idea, protesting that things like love and beauty, tragedy and meaning, might not be measurable, but are just as real as the firing neurons and chemical reactions that they produce.

Oxford physiologist Denis Noble, who features in the documentary, is no stranger to the benefits of reductionism but believes that arrangements of atoms have to be more than the sum of their parts.

“For example, you figure out the molecular structure of DNA,” he says, “and suddenly it’s very natural to think, ‘Well, that is so powerful, it must be the way of explaining everything’. … [But] if I take the DNA out of a cell and I put it in a Petri dish with as many nutrients as you like, I can keep it for 10,000 years. It’ll do absolutely nothing. It can’t be the secret of life.”

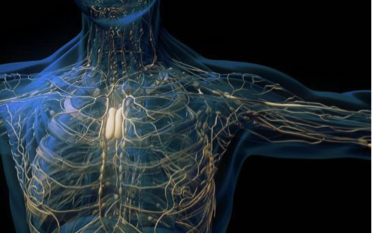

Another scientist we hear from is physicist George Ellis. He suggests that, while we might be able to explain simple life as physics and chemistry, even the existence of thoughts and ideas provides a challenge to pure reductionism. Sure, we can explain what’s going on in the brain in terms of the physics of the molecules, and properties of the neurons – but this doesn’t come close to explaining the ideas and thoughts that are held within that brain.

Another scientist we hear from is physicist George Ellis. He suggests that, while we might be able to explain simple life as physics and chemistry, even the existence of thoughts and ideas provides a challenge to pure reductionism. Sure, we can explain what’s going on in the brain in terms of the physics of the molecules, and properties of the neurons – but this doesn’t come close to explaining the ideas and thoughts that are held within that brain.

Thoughts are not physical – they’re abstract things – but they’re real nonetheless, and drive the physics. Ellis uses the example of a pair of glasses: they have physical properties but once existed in someone’s imagination before they were brought into being. Without the idea, they wouldn’t exist.

“From my viewpoint , existence isn’t just physical existence, there’s these abstract existences,” says Ellis. In other words, if ideas act on the world in a way that isn’t completely dictated by the movement of particles, then – contra scientism – we can accept a non-material reality after all. From this it follows that human beings might in fact be more than complex computers – more like how we tend to imagine ourselves to be, creatures whose place in the universe matters and has significance.

The most captivating aspect of Why are we here? is the interchange between Ard Louis and David Malone. They clearly enjoy each other’s company, while recognising the vast differences in their worldviews. The viewer is left with the sense that the proponents of scientism we hear from are honest and clear-thinking enough to face the far-reaching implications of their position.

Ironically, as Ard Louis recognises, he and the atheistic reductionists like Alex Rosenberg find a strange agreement in this – and Louis is humble enough to admit that it’s possible Rosenberg is right. If you start from the idea that there is truly nothing but atoms and molecules, then it’s inevitable (if you’re honest) that you finish at a kind of nihilism where there is no ultimate meaning, purpose or morality.

If, however, you want to keep those things, you have to assume an objective reality beyond the universe—God, if you like. “What you can’t have,” says Louis, “is those nice things and no God. And that I’m afraid is the position that David is in.”

Malone acknowledges this truth. “I’m the one with the problem. God either exists or he doesn’t. And if you believe he does then there’s no problem with meaning or purpose or any of the things Ard and I agree on. The problem is defending meaning and purpose from reductionist science if you don’t believe in God.”

Malone admits to being bothered by this observation. He believes we are only atoms and molecules and that there is no God but feels deeply that life has purpose. He wants the elementary particles of his cake to mean something as he eats it. “We should be careful of letting go of these intuitions too easily,” says Ard Louis.

Part II of Why are we Here? airs on Saturday 16 July on the History Channel at 6.30 pm.

Simon Smart is the Director of the Centre for Public Christianity.