“This year Amadeo Padilla is Jesus.”

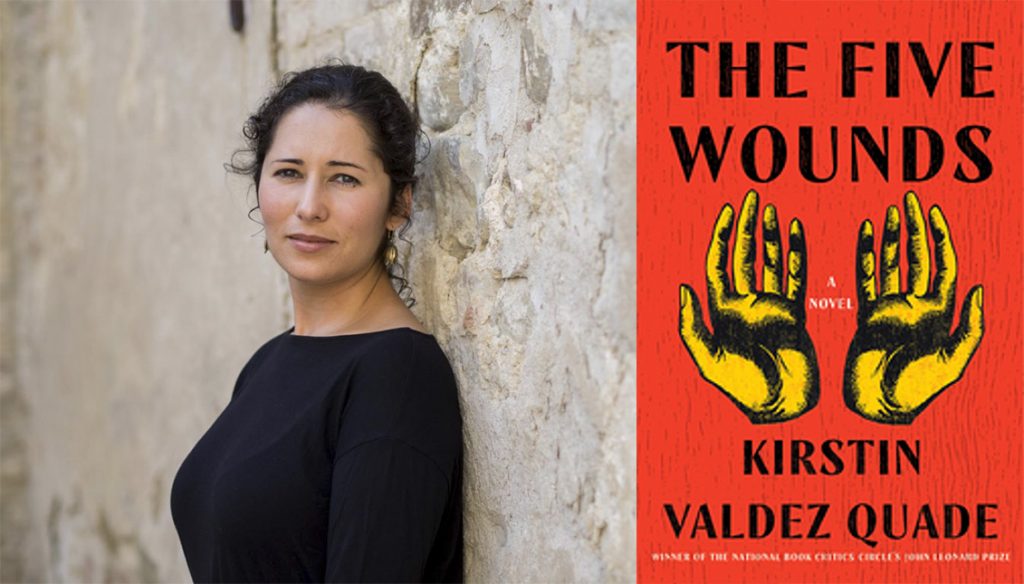

So reads the opening line of Kristin Valdez Quade’s celebrated short story, The Five Wounds, that appeared in The New Yorker in 2009 and this week will hit the shelves as one of the most anticipated novels of 2021.

A glittering array of writers are lining up to praise it, and readers can’t wait to hear more of Amadeo, the unemployed 33-year-old from Las Penas, New Mexico, chosen for the part of Jesus in the annual Good Friday procession. This is no sweet Sunday School re-enactment, however. This community takes its crucifixions seriously.

It’s no coincidence that Easter week was chosen for the release of Quade’s novel, as it picks up the central narrative of the hapless wreck of a man seeking redemption for all the ways his life has gone awry.

“Amadeo is pockmarked and bad-toothed, hair shaved to a scalp scarred from fights, roll of skin where skull meets thick neck. You name the sin, he’s done it: gluttony, sloth, f—ed a second cousin on the dark bleachers at the high school.”

Amadeo knows he’s messed his life up so comprehensively any atonement will have to be hard-won and costly. There will be no cheap grace to overcome his shame – a shame that is perfectly symbolised by the arrival on his doorstep of his 15-year-old pregnant daughter, Angel, in the week he is preparing for Good Friday glory. His neglect of Angel is only the most conspicuous of his many failures and she serves as a very public reminder of why he deserves what he’s about to face. Will he ask for the nails as fellow would-be Jesus, the legendary Manuel Garcia, had back in 1962?

The Five Wounds poses a haunting question—where do we turn to today to atone for our failures and faults; to find freedom from our shame? Writing in The Atlantic last month, Graeme Wood noted that religious traditions have various “earthly” ways of expiating guilt through ritual and confession, but that option seems largely absent in today’s more secular environment.

Wood was responding to the axing of 27-year-old Alexi McCammond as the prospective editor of Teen Vogue for some ugly racist tweets she sent out as a 17-year-old (she apologised in 2019). Wood made the entirely reasonable point that plenty of us wouldn’t want to be haunted by the idiotic things we said as teens.

The case of McCammond, Justine Sacco and others suggests that public shaming is back in vogue, and we can’t get enough of it. Online pile-ons, Twitter storms and media-driven public judgments, in their best light, reveal a frustration with systemic injustice and a sense that too often people get away with unacceptable behaviour. How might we give a voice to the voiceless?

At their worst, they can resemble more primitive public stonings or the burning of heretics in the town square. But either way, where wrongs have taken place, there is a longing for things to be put right. Someone has to pay.

But Jon Ronson’s So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed (2015) raises a disquieting notion: what if the vitriol of the mob is a way of dealing with our fears that this could happen to me?

“We all have ticking away within us something we fear will badly harm our reputation if it got out,” writes Ronson. “Maybe our secret is actually nothing horrendous. Maybe no-one would even consider it a big deal if it was exposed. But we can’t take the risk. So we keep it buried.”

In our high-risk contemporary culture of shame, becoming re-acquainted with the original Easter story could turn out to be surprisingly healing.

Kristin Valdez Quade’s Amadeo Padilla felt he didn’t have that option. Pinned to the cross in the most shocking and confronting manner and lifted above the astonished crowd, he has an epiphany – a moment of piercing moral clarity in the midst of physical agony: “This is all wrong,” he thinks. “I am not the son.” He can’t be Jesus. Not even for a day.

Amadeo’s journey towards a hoped-for restitution is ultimately doomed because of an essential element of the most famous crucifixion in history. It is only God who can bear the weight of the world and all its sorrows.

In our high-risk contemporary culture of shame, with no obvious paths back from the social wilderness, becoming re-acquainted with the original Easter story could turn out to be surprisingly healing. It is, after all, about someone else taking on and expunging the record of missteps, failures and sins. Even very serious ones. That’s something hopeful for all of us, whether or not we have managed to escape the censure of the crowd.

Simon Smart is the executive director of the Centre for Public Christianity.

This article first appeared in The Sydney Morning Herald.