In my work as a college lecturer I occasionally ask my students the following question: In the last 60 years, which person has had the greatest impact on our sex lives? There is, of course, no one correct answer, and the diversity of responses I have received bear that out: Madonna, Lady Gaga, Masters and Johnson. But personally, I would stump for Frank Colton as my candidate. Colton was the American chemist who developed Enovid, the first oral contraceptive. And without the “pill,” I would hazard a guess that the 1960’s would have turned out very differently. The headline of “free love” was underwritten by a technological breakthrough.

The lesson of the “pill” is that the way we structure our relationships does not take place in an ahistorical fashion. We mediate our loves and desires, and our expressions of hunger and passion, through concrete cultural circumstances. That baseline desire to relate, to know and be known, to feel and to be touched, remains remarkably constant. But the forms and shape of relationships are altered by all manner of inventions, from our built environment all the way through to handheld technologies. As Andy Crouch has argued in his book Culture-Making, the bringing into existence of any cultural artefact always creates both possibilities and difficulties.

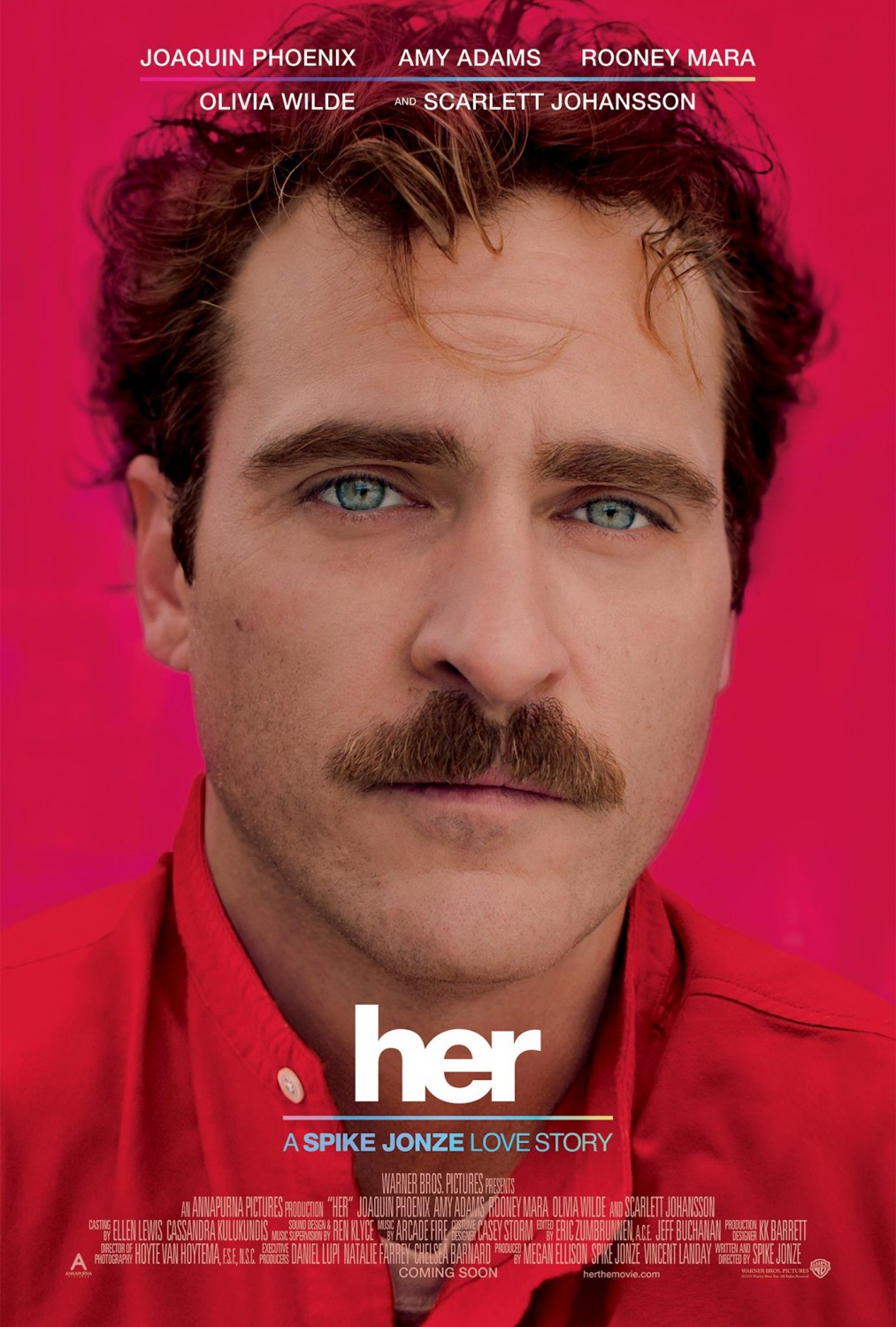

The imagined future of Spike Jonze’s latest film, Her, is not all that far removed from our own moment. The story takes place some way into the future, a point at which smartphones employ an artificially intelligent operating system, which is able to create a persona tailored to the individual needs of the user. In simple terms, the ‘Siri’ of our age has evolved into a fully orbed companion, capable of being your confidante, and even, perhaps, your girlfriend.

The central character of Her is Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix), a reclusive loner who retreats easily to his apartment, and his interactive video games. Twombly is a divorcee, and appears uncomfortable with himself and with others, unable to summon the commitment and vulnerability required to sustain a romantic relationship. Enter Samantha, voiced by Scarlett Johansson, the operating system that helps make Twombly’s life not just bearable, but actually enjoyable.

This scenario enables Jonze to explore a whole host of intriguing topics, many of which examine life from the perspective of a digital character. To what degree can an electronic device ever attain to the status of a person? Of particular concern is the nexus between embodiment and human personhood, including several moments where Samantha longs to be completed through experiencing some kind of incarnation.

But ultimately Samantha progresses to a place where she sees herself as fundamentally different from human beings, recognising that she belongs in a place that’s not of the physical world (a cyberspace heaven?). At one point Twombly is shocked to discover that Samantha is in hundreds of intimate relationships, unshackled as she is by physical constraints.

This focus on the promise and limitations of embodiment is nothing new in cinema, but the topic is worth revisiting in our digital context, in which we can spend our whole day communicating without ever being in the same space as another body. By demonstrating that Samantha is not like us, the storyline of Her implicitly affirms that the human body, and its full sensual repertoire, is quintessentially part of our identity. We ignore it and neglect it at our peril. In other words, true relationship with anything like a computer is out of the question.

Yet it is the embodied characters that are the most problematic in Her—those who in one sense have it all but somehow don’t know what to do with it. Despite his social inadequacies, by day Twombly works as a letter-writer at BeautifulHandWrittenLetters.Com, where he composes impassioned love notes and heartfelt birthday messages for customers who feel verbally inadequate. And Twombly is good at his job, showing a remarkable gift to learn the story of someone else’s relationship, and then compose a message that fits perfectly. He only struggles for words when his own relationships are on the line.

This feature of Her’s narrative world, in which people subcontract out even the language of their love, is one of its most poignant comments on trends of contemporary life. The wonders of e-commerce, and the easy transfer of words and images, mean we now inhabit a cultural moment where it is just easier to outsource our most intimate moments.

But at some point we have to have dinner.

Indeed it is often the meal scenes of Her that the real awkwardness of human relations emerges. Perhaps a technology will one day be invented that will ameliorate the problems of stilted conversations and embarrassing gestures, but until such time, the dinner table retains a power of authenticity, however ugly we might find our real self to be.

Our devices often hold out the promise of overcoming our bodily limitations, in both time and space. But in seeking to transcend the body, we end up finding how essential it is to human existence. And by never relinquishing our hold upon our phones, we fail ourselves and the people who are right in front of us.

The best of relationship happens face to face and the intimacy we crave is found in being fully present to the other, in both soul and body. It has always been so. The Christian story presents humans as being irretrievably “fleshy” from the beginning. Indeed, the first human creature “Adam” speaks of one made from the earth, and human life at its best is always construed as located, physical, and sensuous.

Moreover, the end of the story is not the freeing of an immortal soul from the prison-house of the flesh, but rather a transformed embodiment in which death and frailty are overcome. The Christian vision is not of the body rejected, but the body perfected. That’s an incredibly positive account of reality that urges us to come to terms with our embodiment, to accept its limitations, yes, but more than that, to revel in the way that it focuses our attentions, provides us with pleasure, and enables us to know one another wholly.

Dr Mark Stephens is a lecturer in Biblical Studies at the Wesley Institute and a Fellow of the Centre for Public Christianity.