In his Easter message last year, British Prime Minister David Cameron was not the least bit shy about identifying his country’s religious foundation. “Yes, we are a nation that welcomes, embraces and accepts all faiths and none”, he said, “but we’re still a Christian country.”

No politician would get away with that in Australia. The first church built here was burnt to the ground by the convicts and ever since we’ve had a somewhat uneasy relationship with organised religion.

But despite our apparent lack of religiosity, as a culture we remain thoroughly marinated in the juices of an ancient story, the climax of which is celebrated around the country this weekend. The first Easter Sunday led to claims of an empty tomb and, in the West, life has never been the same since.

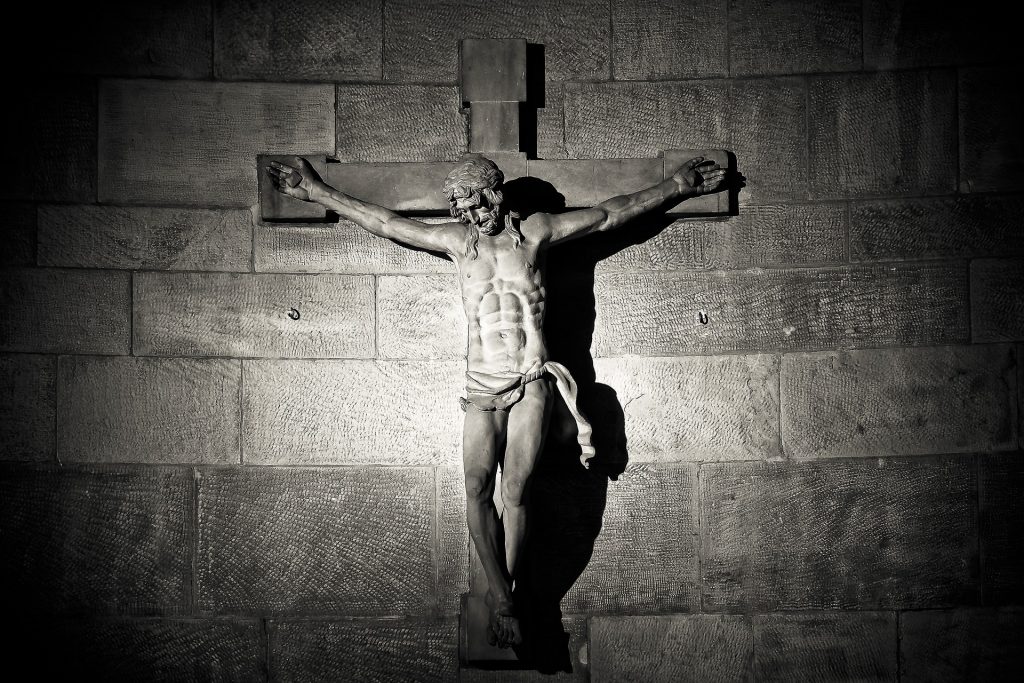

The reality is, despite fewer and fewer of us having a hope of being able to articulate the details of that story, it is ingrained in the fibre of Western history as the moment when a revolutionary understanding of the value of every individual germinated and began to grow. The idea that the creator of the universe would enter the human drama as a child and then, in order to redeem it, willingly submit to a brutal and humiliating death, shaped our culture in profoundly important ways.

The Jewish tradition of the poor being the ones God loves was picked up and extended by early Christianity and its account of the crucifixion. For educated people in the ancient world, the grotesque execution of Jesus was the worst kind of humiliation, one that couldn’t possibly have anything to do with divinity. But for the Christian, this humiliation was profoundly meaningful – salvation itself! The low point became the high point – the great inversion. Jesus urged those who wanted to be great, to also become the servant, or slave, of all.

Atheist philosopher Alain de Botton recognises the value of this radical shift:

“Among Christianity’s greatest achievements has been its capacity, without the use of any coercion beyond the gentlest of theological arguments, to persuade monarchs and magnates to kneel down and abase themselves before the statue of a carpenter, and to wash the feet of peasants, street sweepers and dispatch drivers.”

The idea that those without status were actually the unique concern of God represented a radical enunciation of an ethos Westerners now consider self-evident but that was hitherto unimaginable.

“One finds nothing in pagan society remotely comparable in magnitude to the Christian willingness to provide continuously for persons in need, male and female, young and old, free and bound alike”, says historian and theologian David Bentley Hart.

It had a lasting impact. People now simply take it for granted that institutions of public welfare, like free hospitals and soup kitchens or free education, are a social good whether or not they are economically beneficial. We may only pay lip service to care for the marginalised, but we do so knowing this is a moral good, even a moral responsibility. Over the centuries people absorbed this sensibility into their moral DNA, and while there have been terrible failures along the way, the world is a substantially kinder, more compassionate place than it would otherwise have been.

And it matters where these foundational concepts comes from. The great atheist critic of Christianity, Friedrich Nietzsche, insisted that the death of God meant the death of objective morality. Having lost the transcendent, the ground on which ethics rests becomes decidedly unsteady.

It’s worth pondering the foundation on which some of our most treasured convictions rest – and asking ourselves what it is that gives them the resonance of both beauty and truth.

Australian moral philosopher Raimond Gaita – who is not a believer – writes that only someone who is religious can speak seriously of the sacred, but such talk nonetheless informs the thoughts of most of us whether we are religious or not.

“We may say that all human beings are inestimably precious, that they are ends in themselves, that they are owed unconditional respect, that they possess inalienable rights, and, of course, that they possess inalienable dignity. In my judgment these are ways of trying to say what we feel a need to say when we are estranged from the conceptual resources we need to say it … Not one of them has the simple power of the religious way of speaking.”

There’s no doubt we are losing that way of speaking and thinking. Many will think that is a good thing. But this weekend, whether you combine hot cross buns with hymns and prayers or are more focused on getting your boat out onto the water or your campground sorted, it’s worth pondering the foundation on which some of our most treasured convictions rest – and asking ourselves what it is that gives them the resonance of both beauty and truth.

This article first appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald.

Simon Smart is Director of the Centre for Public Christianity.