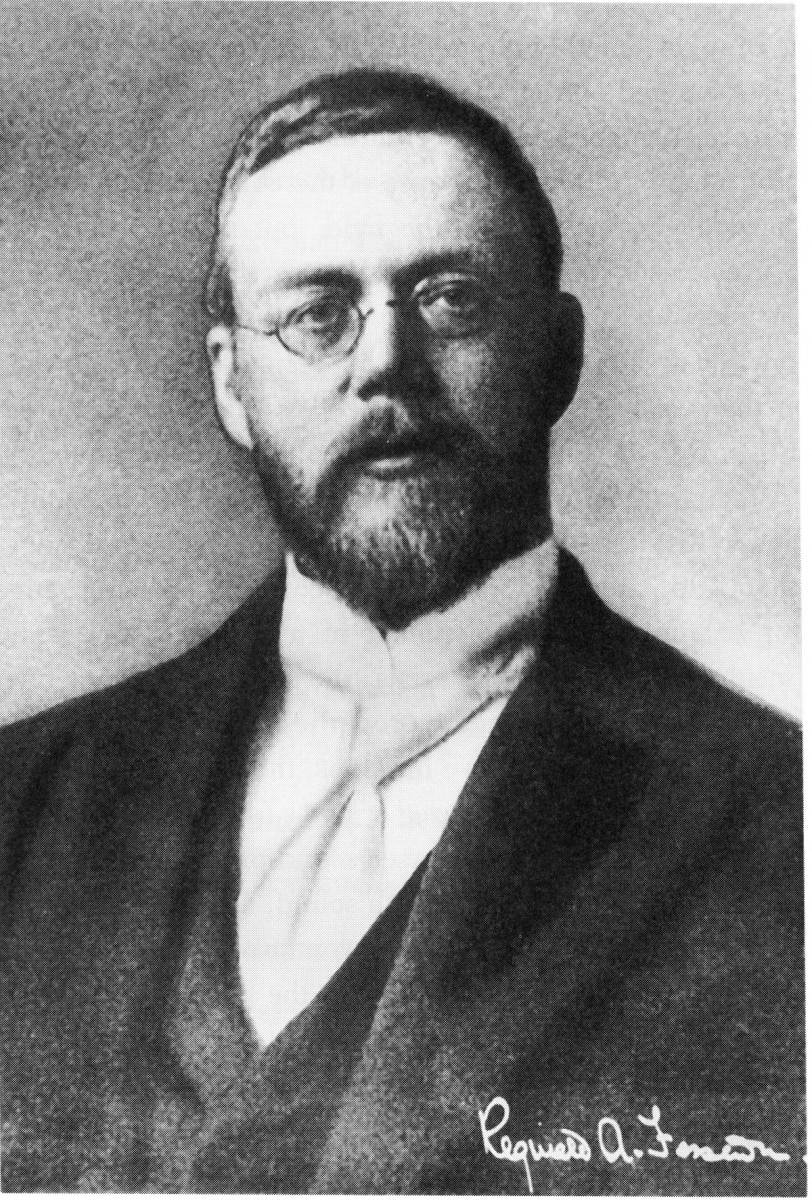

Christmas Eve, 1906. Professor Reginald A. Fessenden, in Brant Rock, Massachusetts, plays a recording from Handel. Then he takes up his violin and plays “O Holy Night.” He reads aloud a passage from the Bible: “And, lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them …”

It was, so far as we know, the first radio broadcast ever made.

The audience would have been chiefly radio operators on ships along the east coast of America. The U.S. Navy had been broadcasting daily time signals and weather reports since 1904, but in Morse code. It must have been eerie to hear a human voice, and the strains of a well-known carol, emerge without warning from their transmitters as they sat at their posts on Christmas Eve.

I find this a strangely moving picture. I like that Fessenden – a Canadian inventor who in 1886, at the age of 19, moved to New York in order to talk Thomas Edison into giving him a job – chose to read this passage in particular.

It’s from the Gospel of Luke, and tells the story of shepherds minding their own business (sheep) in the fields around Bethlehem when suddenly, the whole place is blazing with light and an angel is declaring “good tidings of great joy” for all people, in the form of a baby boy lying in a manger in the town just yonder.

The shepherds are “sore afraid,” the King James Bible reports. They’re freaked out. But they debrief among themselves, and decide to go and see the child. And once they have, they can’t shut up about him; they transmit the message on, spreading wonder and amazement.

We have no record of the response of those radio operators to the same message in 1906. Fessenden concluded by wishing them a merry Christmas, announcing that the program would be repeated in one week, on New Year’s Eve, and urging listeners to write in if they could hear him.

You can imagine him, speaking into an unproven device, sending soundwaves out into the void, hoping somebody is on the other end. Checking the mail all that week, looking for some return to his message. Standing on the cusp of a new epoch in human communication.

The repeat of Fessenden’s miscellaneous Christmas program on 31 December was supposedly heard as far south as the Caribbean; later transmissions from the Brant Rock Station made it across the Atlantic, to the west coast of Scotland. This at a time when the human voice had never been heard, live, disconnected from the immediate vicinity of the person to whom it belonged.

These are astounding distances – dwarfed, however, by another Christmas Eve message delivered more than 60 years later.

The Apollo 8 mission was originally conceived as a test run for the lunar module (later used in the Apollo 11 moon landing), within Earth’s orbit. Instead, astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and William Anders spent the night before Christmas, 1968, orbiting the moon. They became the first humans to leave Earth’s gravitational pull, the first to see the dark side of the moon, and the first to view all of Earth from space.

These guys also opened the Bible for a Christmas message back to Earth. It was the most watched television event in history up to that point. Looking at the planet in its entirety in a way no one before them had ever done, they went back to the beginning, and between them read out the creation account in Genesis 1:

“In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth … And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, ‘Let there be light’ … And God called the dry land Earth; and the gathering together of the waters called he Seas: and God saw that it was good.”

“And from the crew of Apollo 8,” Borman concluded, “we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you, all of you on the good earth.”

Naturally, a culture draws on its shared sacred texts at such moments. Where might we turn now, on a comparable occasion, for words of suitable solemnity and beauty and joy?

The news of a Creator God, showing up as a baby in a manger, is unlikely to be broadcast from the surface of Mars anytime soon. But it will be noised abroad in countless places across the earth this Christmas.

Not, perhaps, by means of epoch-making new channels. But many will find it still as startling and as wondrous as those shepherds who stood in awe while “the glory of the Lord shone round about them,” and a voice from the outside broke in, declaring peace on earth, and good will to all.

Natasha Moore is a Research Fellow with the Centre for Public Christianity. She has a PhD in English from the University of Cambridge and is the editor of 10 Tips for Atheists … and Other Conversations in Faith and Culture.

This article first appeared at ABC Religion & Ethics under the title “‘Good Tidings of Great Joy’: It’s No Wonder We Keeping Tuning in to the Bible”.