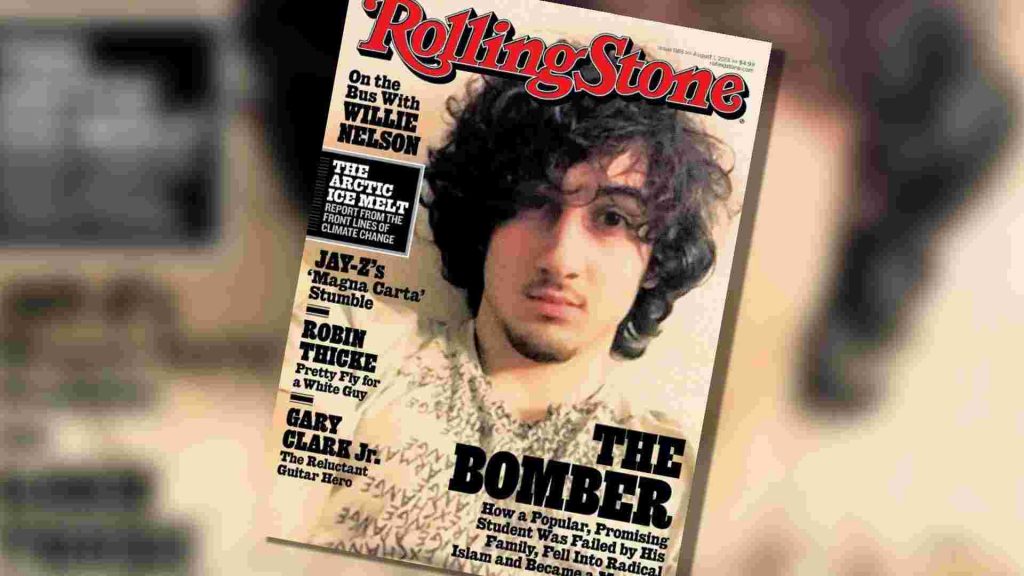

While Rolling Stone sought to defuse the controversy over its cover image of Boston bombing suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, and news articles paraded experts condemning Tsarnaev’s glorification, Yale University theologian Miroslav Volf cut through the firestorm. He tweeted: “We don’t like the evildoer looking like one of us. Perhaps because all of us are a bit like him?”

It’s a provocative thought. While few among us could even contemplate committing mass murder Tsarnaev’s cherubic features disturb our categories of good and evil. The fact that the photo at the centre of Rolling Stone’s current woes is one Tsarnaev took of himself, and one that resembles millions of other selfies on social media, is also unsettling. In an uncanny, uncomfortable way, this ‘charming kid turned monster’, as the magazine goes on to chronicle, could be any one of us. He certainly looks it.

Meanwhile closer to home World Vision CEO Tim Costello declared that it was politically convenient for Australians not to humanise drowned asylum seekers because seeing their faces or learning their names would make them a lot more like us. Costello acknowledges that the suppression of this information may be due to religious and cultural sensitivities, but he suspects the political reasons are paramount.

It seems we can’t stand bombers on magazine covers for the same reason it’s more convenient for dead boat people to remain nameless and faceless – because they resemble us too much.

The kind of image they reflect back to us isn’t all that pretty either. Tsarnaev reminds us that even angelic-looking boymen are capable of great evil. Our callous treatment of asylum seekers – in May, excising the Australia mainland from the migration zone to further impede their claims to asylum, leaving them dead in the water in June, and now shielding ourselves from their humanity by denying them names – represents the grossest failure to love the vulnerable others in our midst.

These stories can’t help but strike a nerve when our media has recently debated our tendency to manufacture a polished self-image that we can project to the world.

Today we present our Facebook selves in only the most attractive light possible, constructing an airbrushed identity designed to accrue the admiration of others.

If we’re really serious about seeing ourselves as “we really are” we can start by looking into the faces of those that confront us with our own flaws.

Adam Hills cheekily contributed to this discussion by suggesting the introduction of the “daggy selfie”. “It’s about time we reclaimed our own image by posting realistic photos of ourselves,” he says. “The kind of photo that shows us for who we really are. Fragile, hopeless, confused humans with flaws both internal and external.”

Hills shows us what he means by posting a mildly unflattering photo of himself posed awkwardly on a couch. He’s being cute (that man can’t be anything else, especially with his waistband hiked right up) but he makes a serious point. The kind of selfie he has in mind is refreshingly honest compared to our manufactured self-portraits.

But if we’re really serious about seeing ourselves as “we really are” we can start by looking into the faces of those that confront us with our own flaws. They remind us that even the most unassuming among us are capable of committing wicked acts just as much as they reveal that our failure to act in the face of others’ suffering, or even acquaint ourselves with it, is its own kind of cruelty.

This isn’t a cry for self-flagellation so much as it is a call for us to simply be honest about our own failings, mourn them, and consider how we might act differently in future. It’s a call for – if this isn’t too churchy a word – something approaching ‘repentance’.

I don’t know what such a ‘repentant selfie’, might look like but it takes courage to see ourselves as we really are. It’s too bad that too often human frailty is a truth that’s too inconvenient to face.

Justine Toh is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity and an Honorary Associate of the Department of Media, Music, and Cultural Studies at Macquarie University.

This article originally appeared at news.com.au